Film Friday: Victorian Mustache Fashion

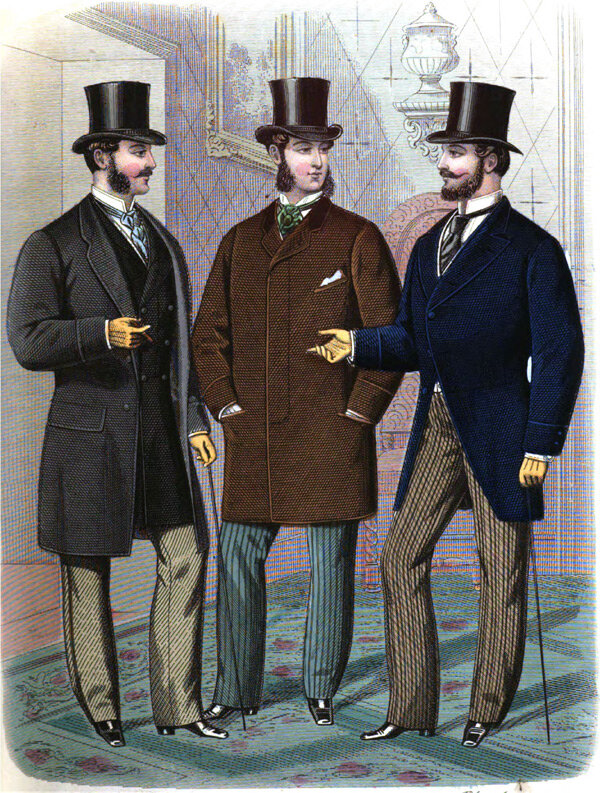

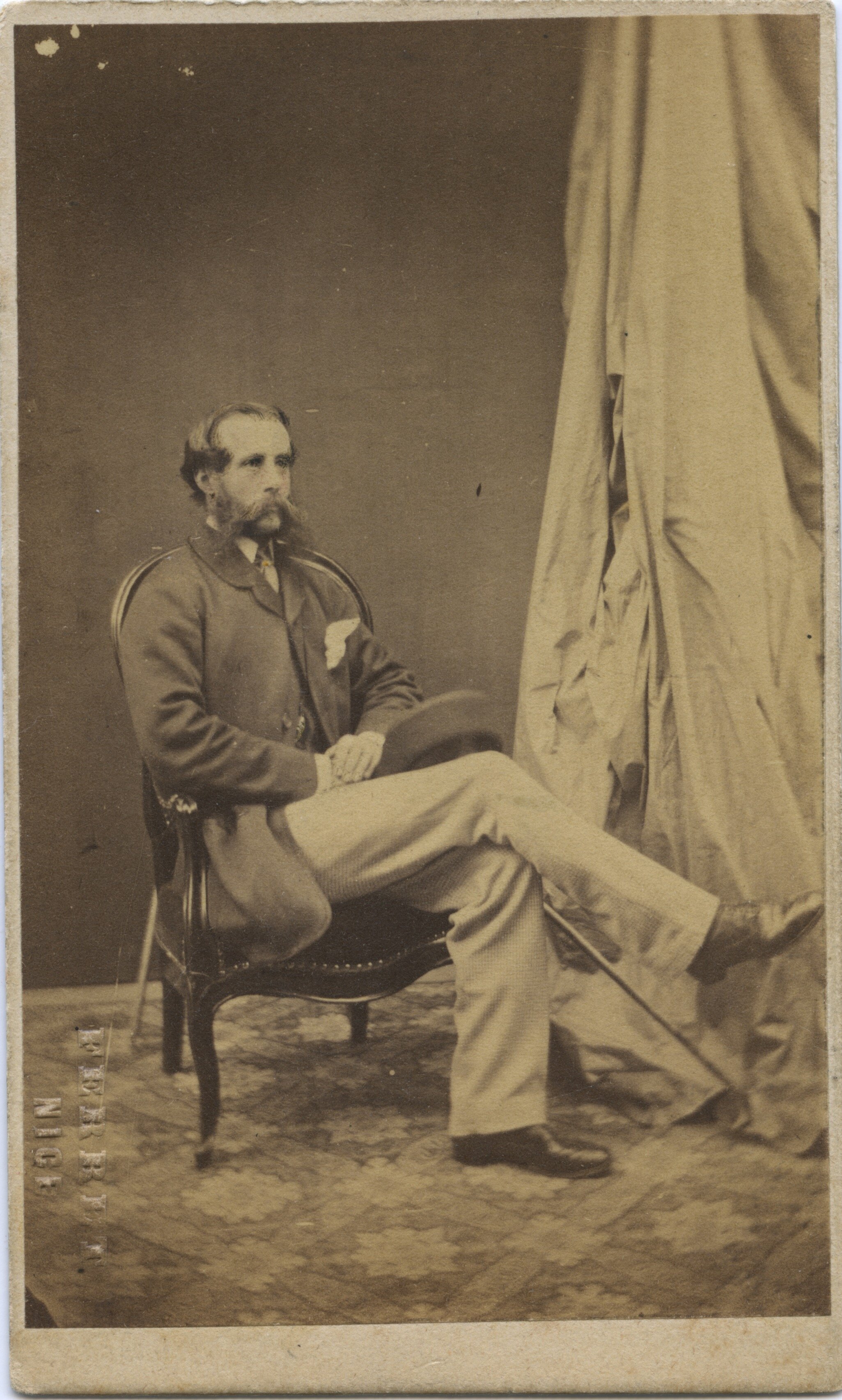

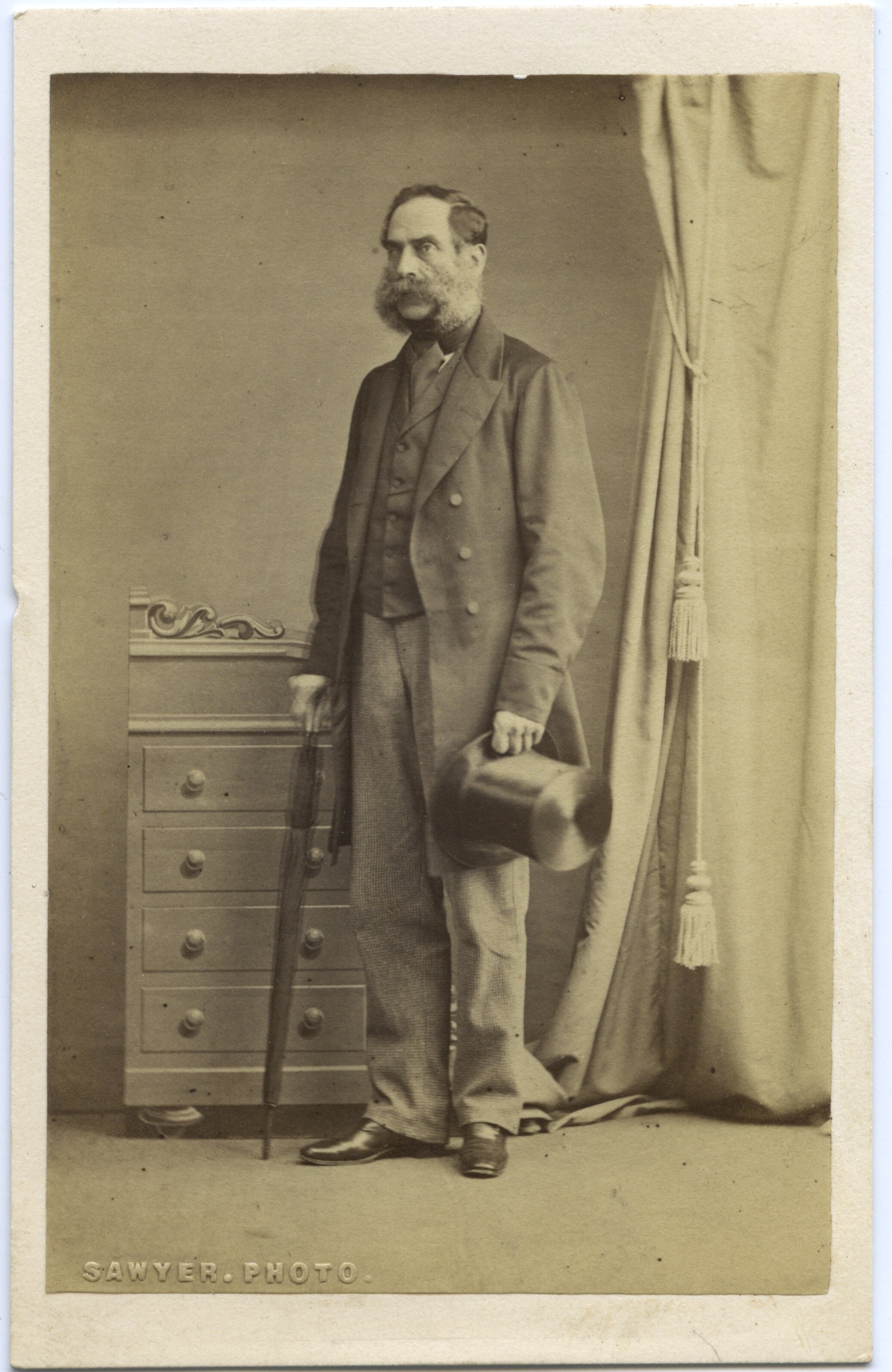

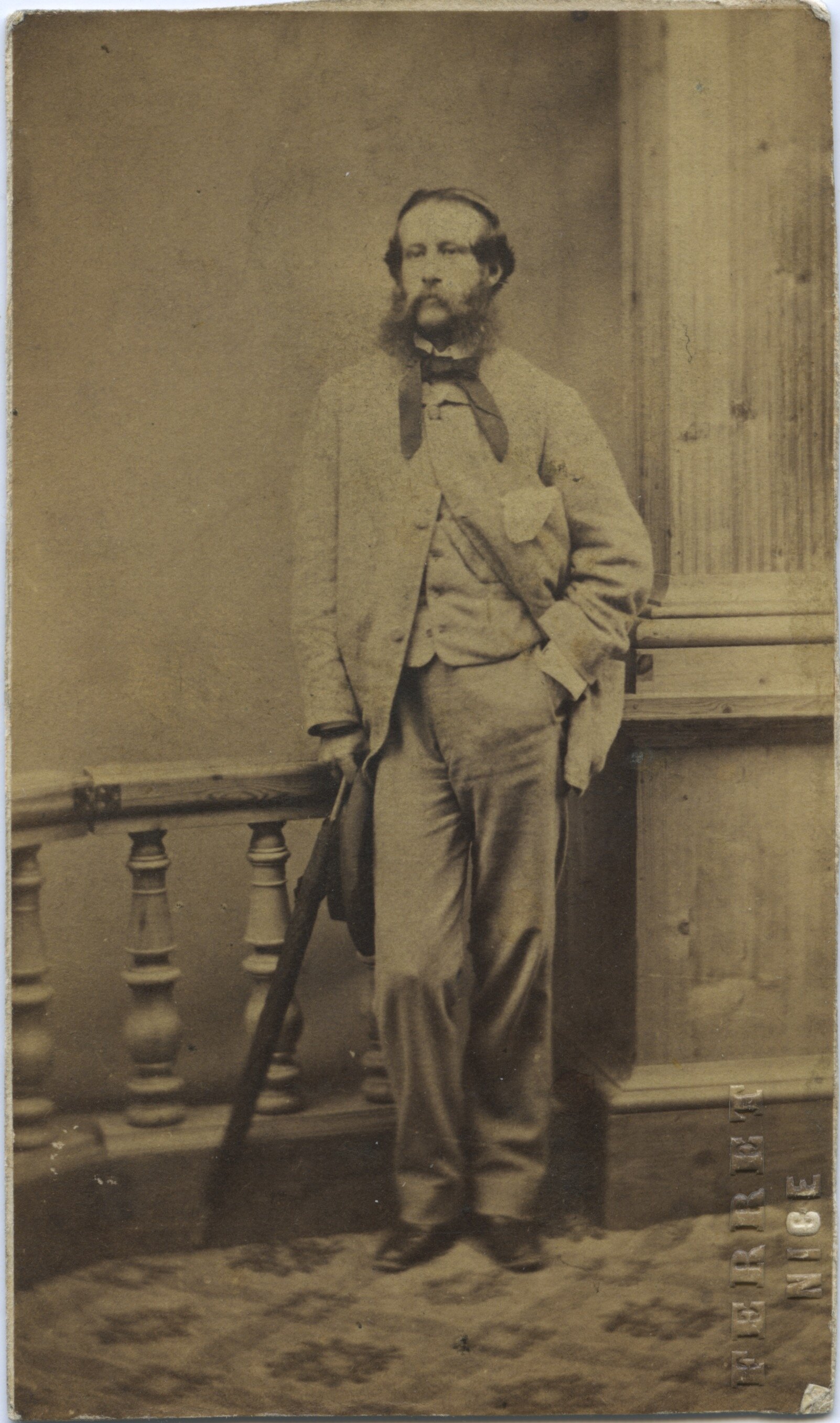

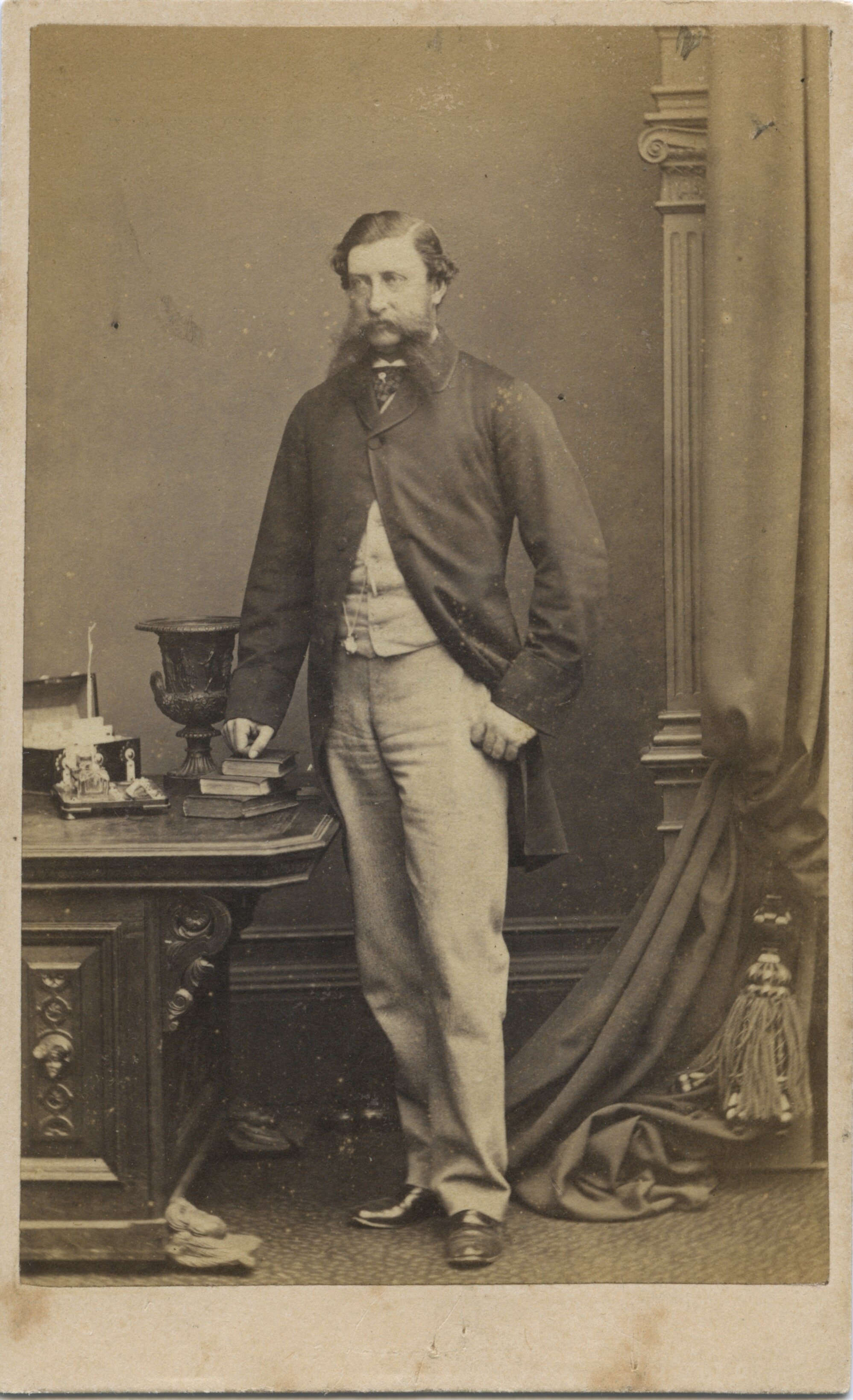

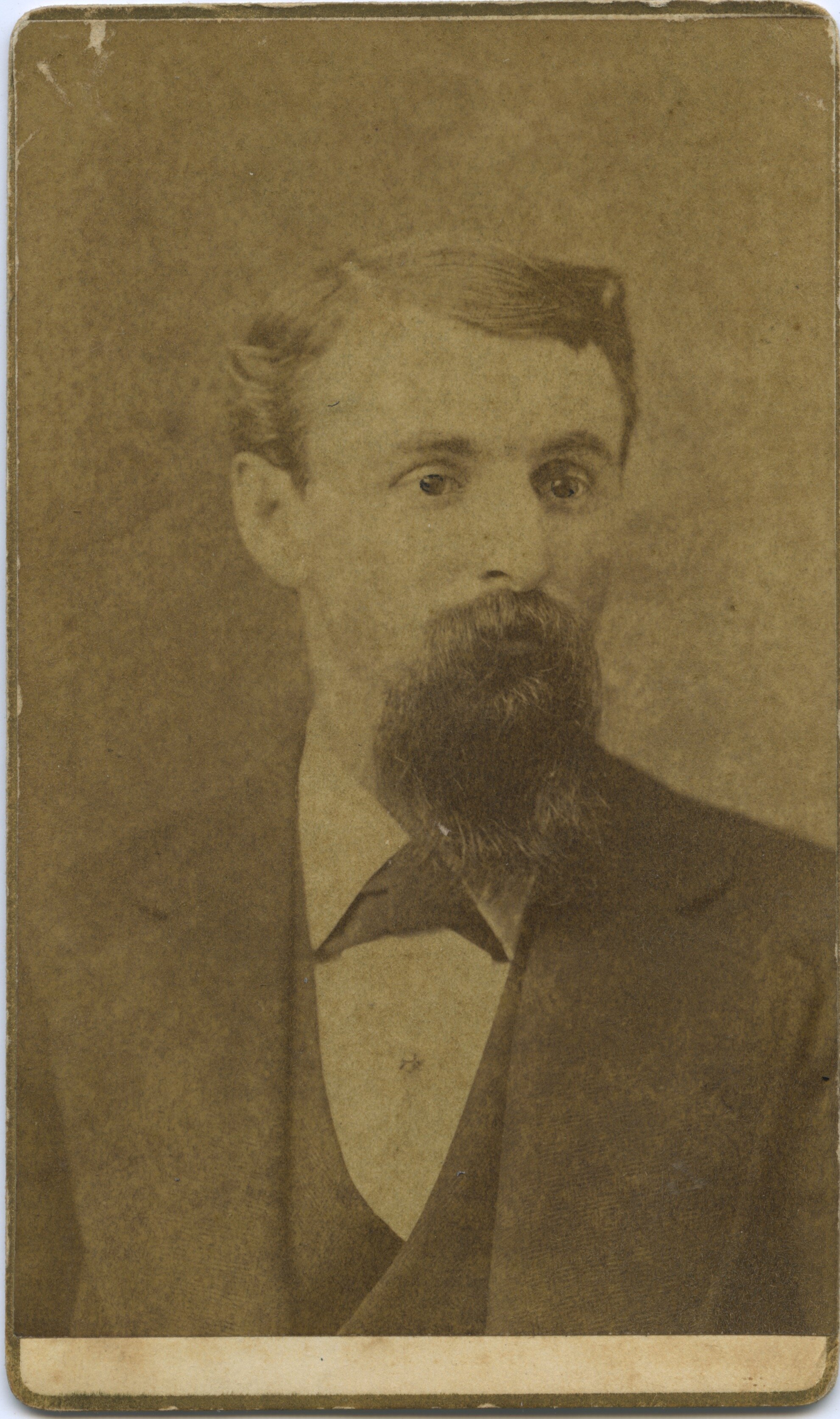

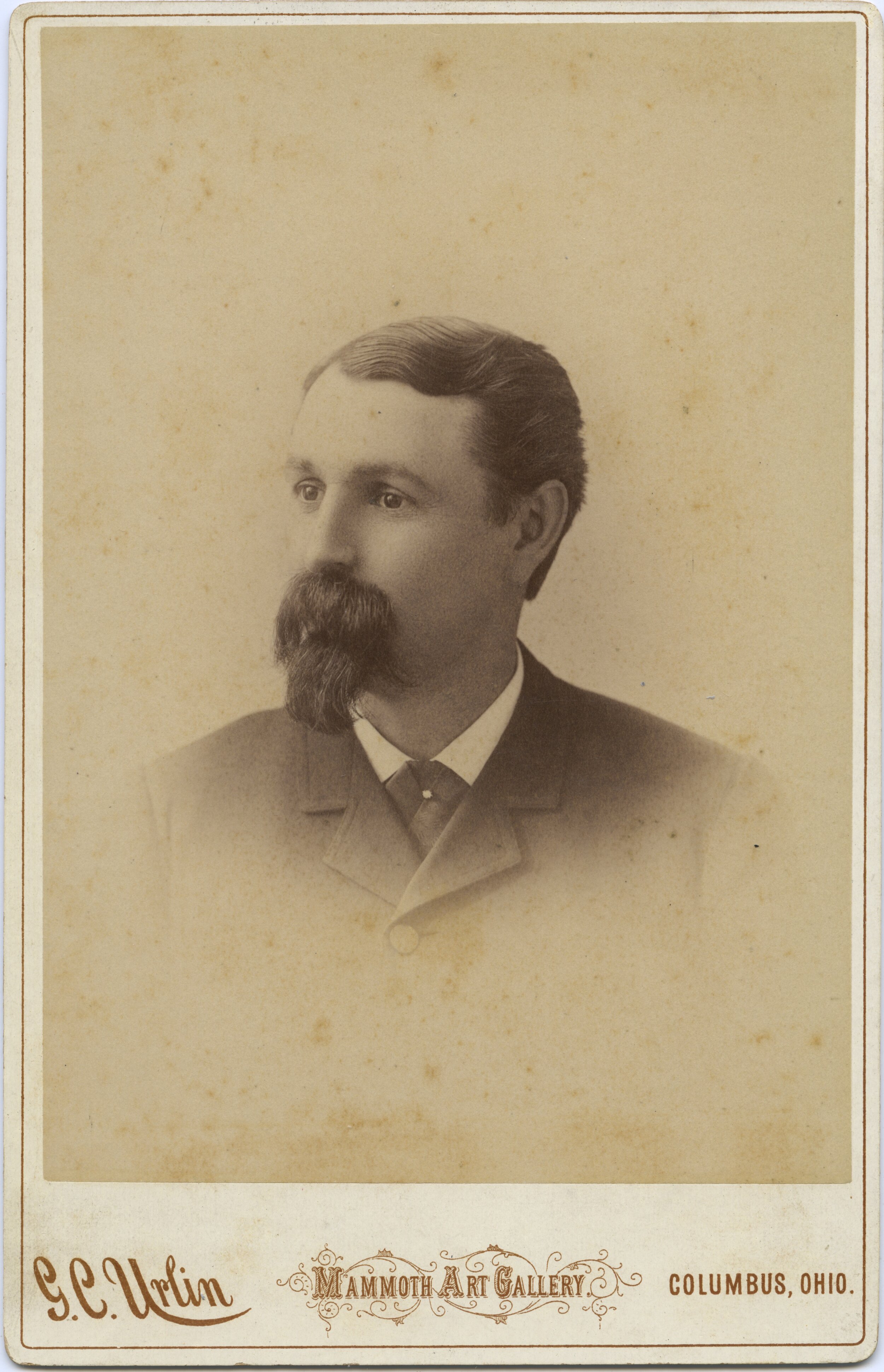

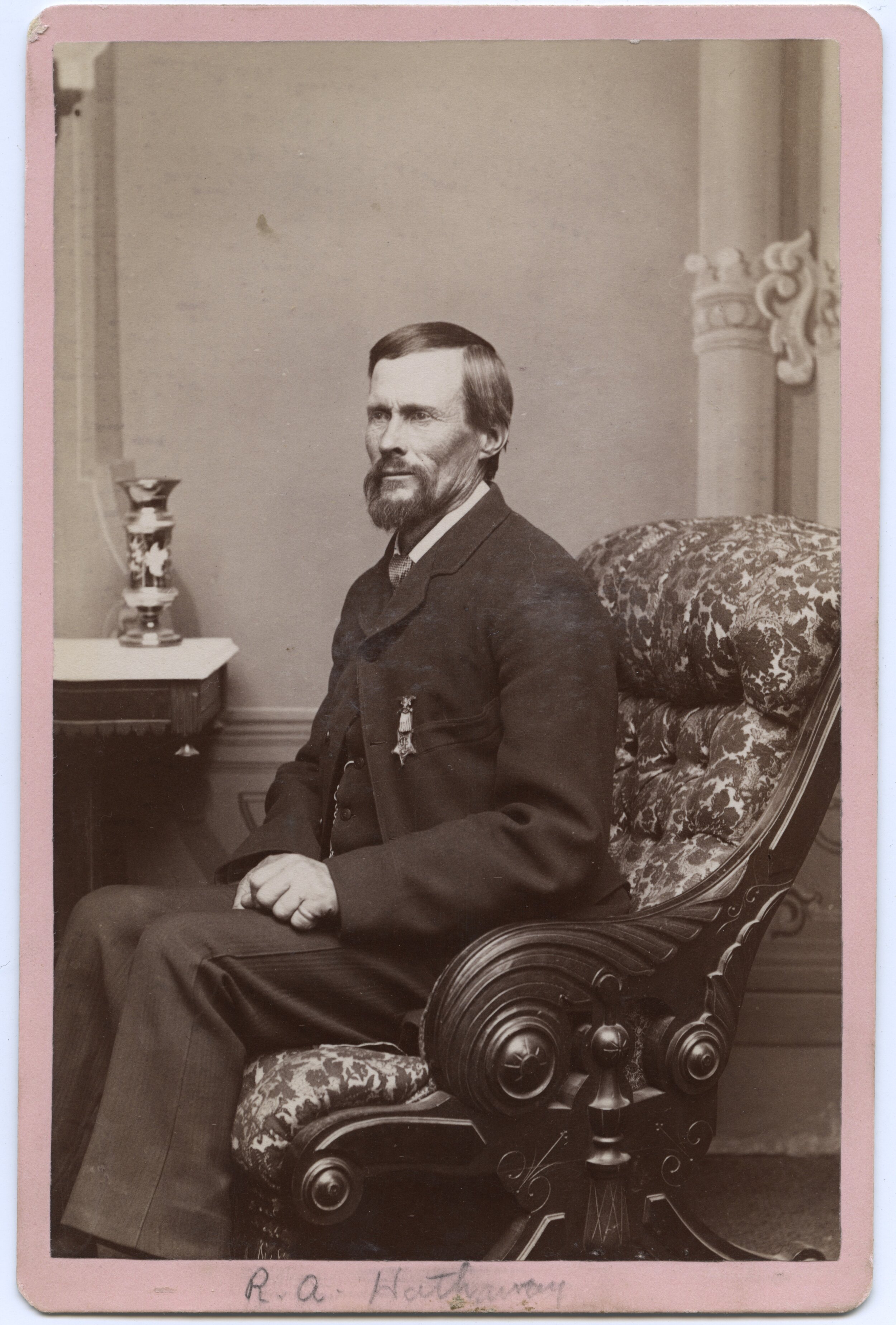

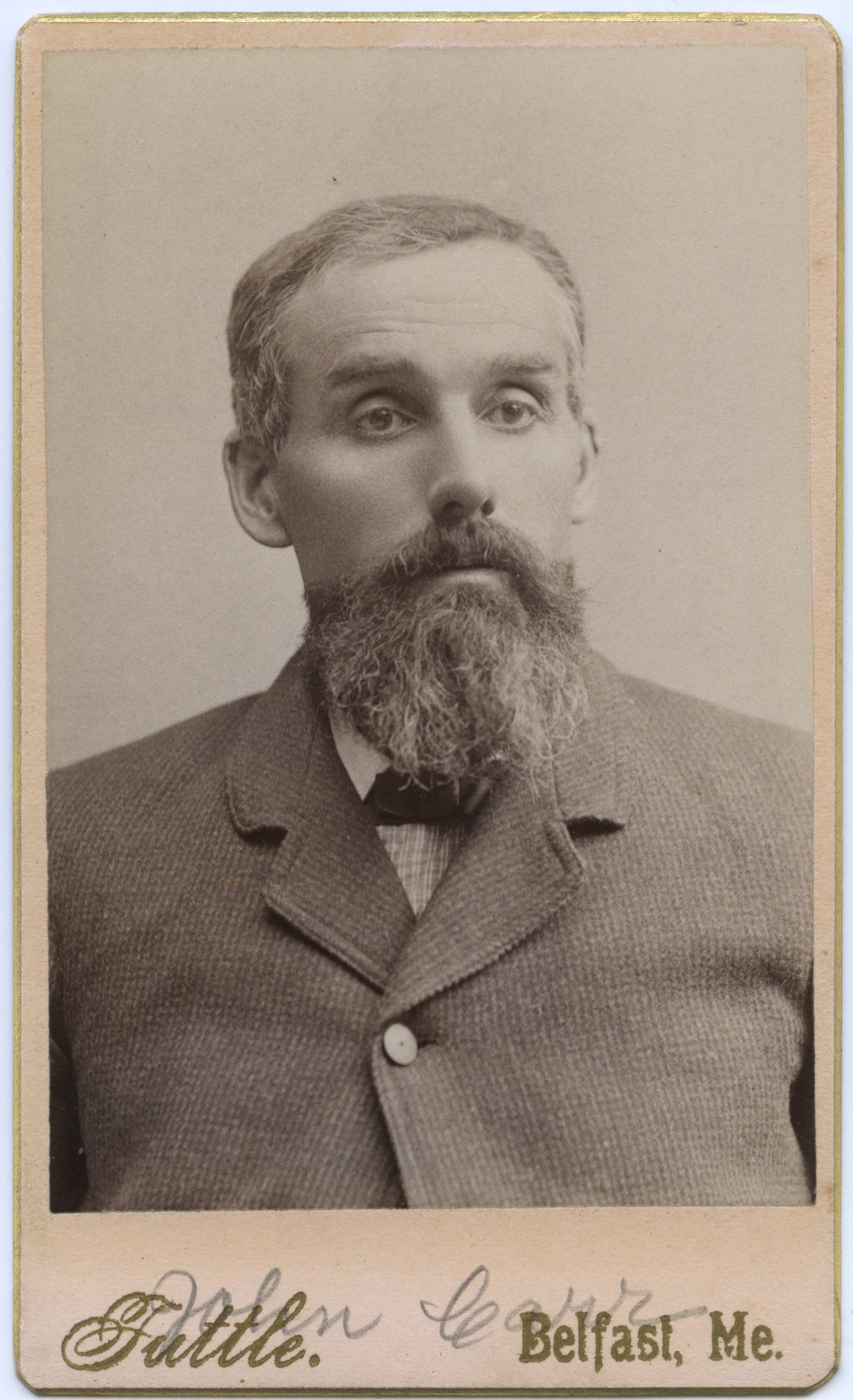

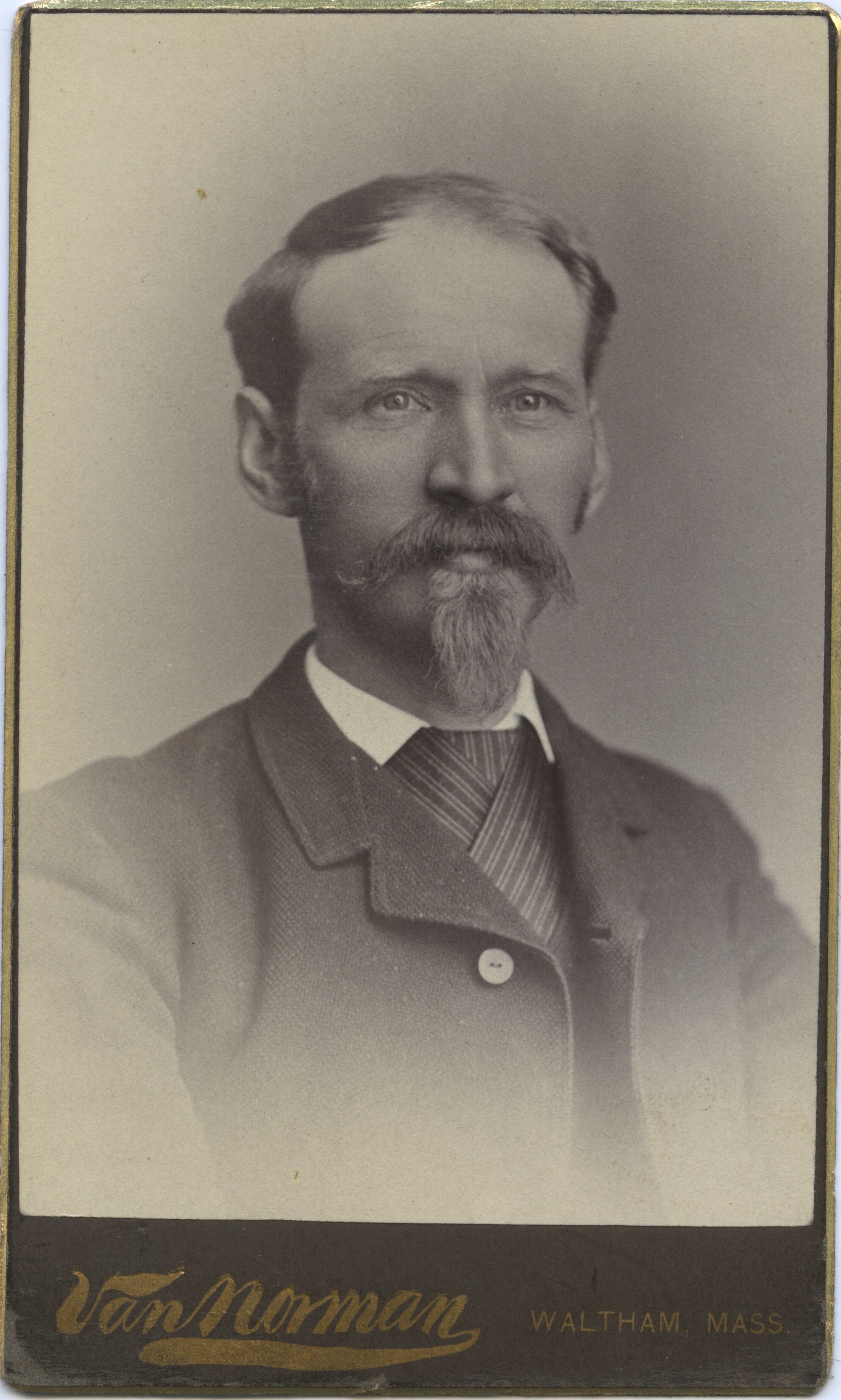

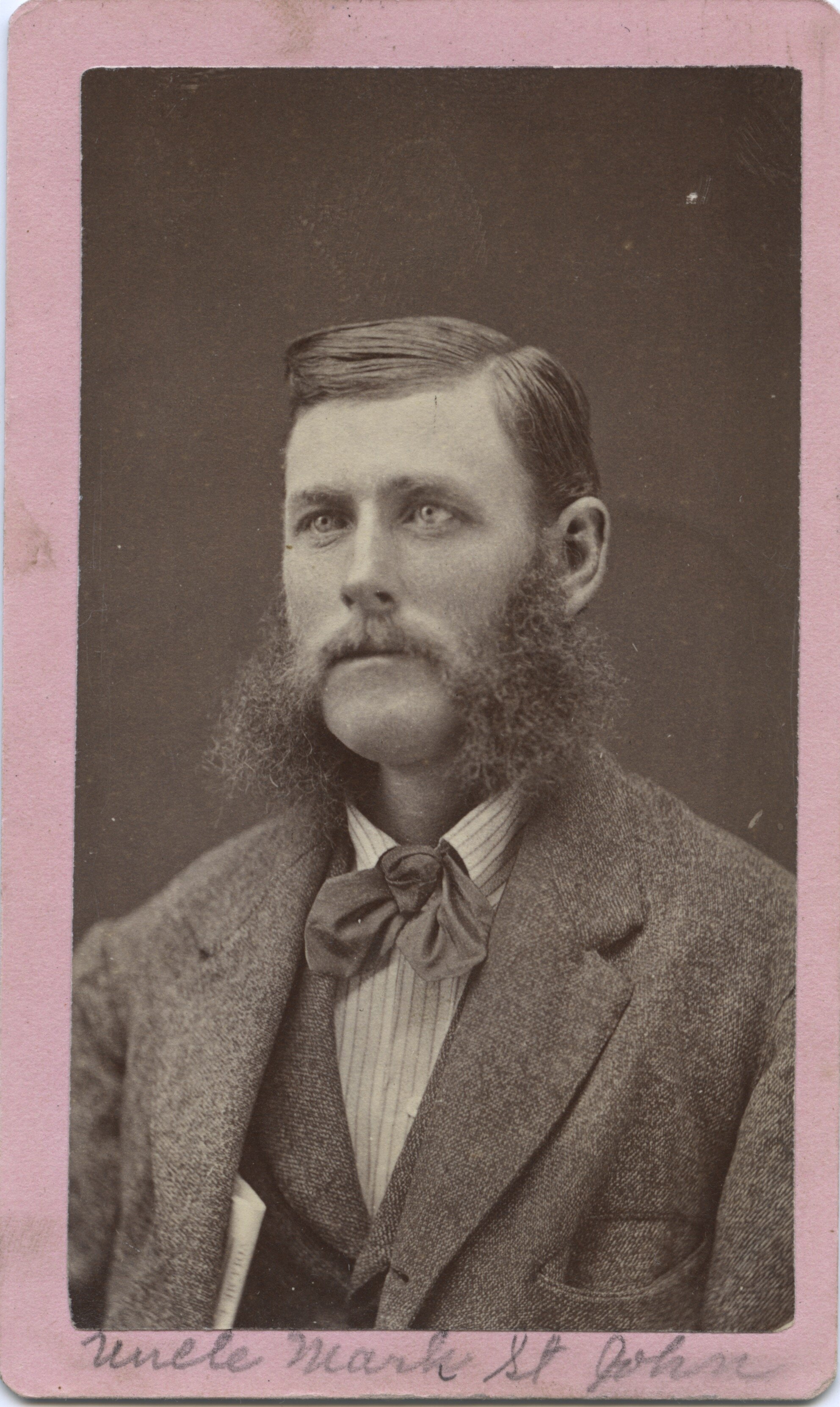

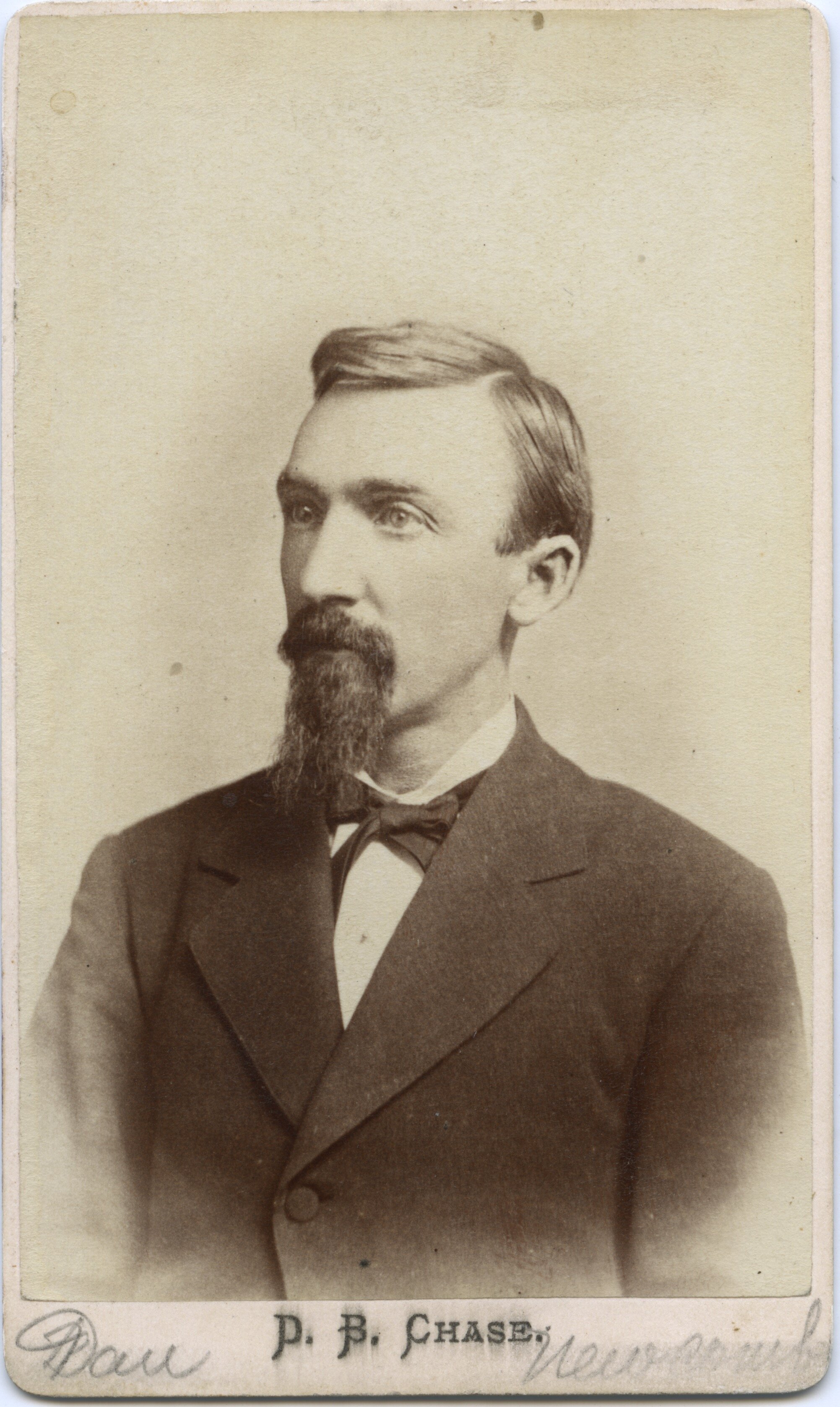

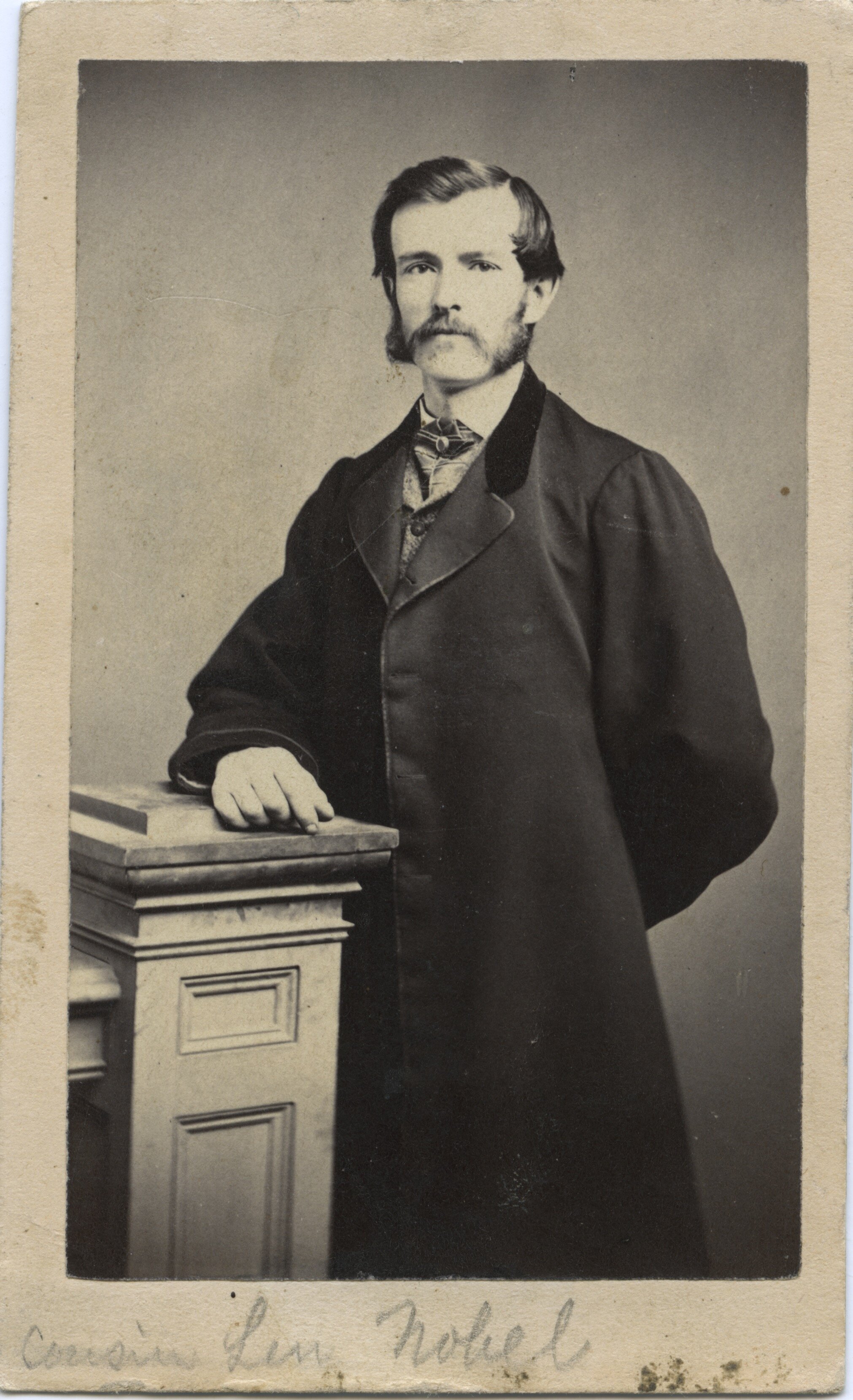

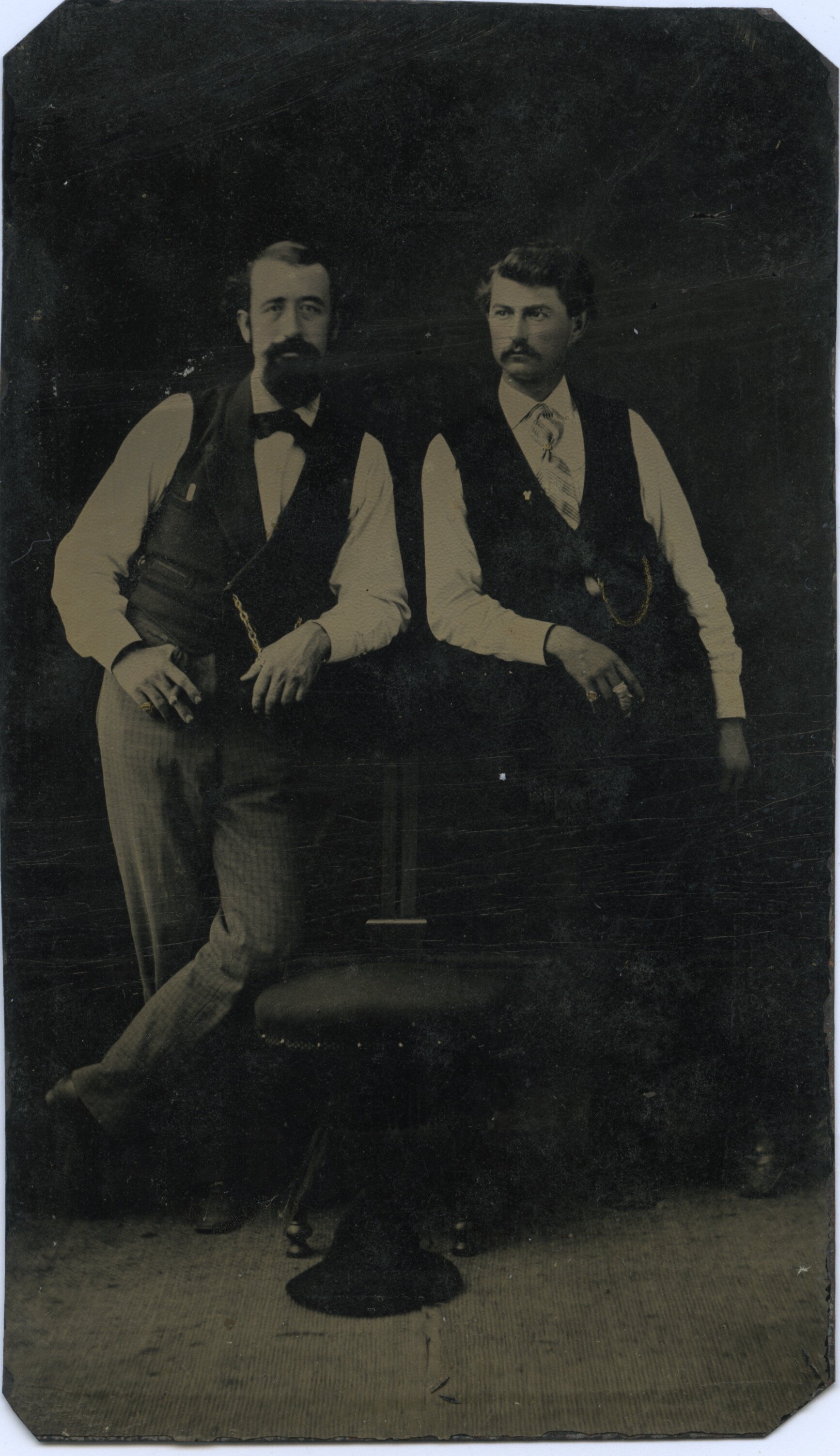

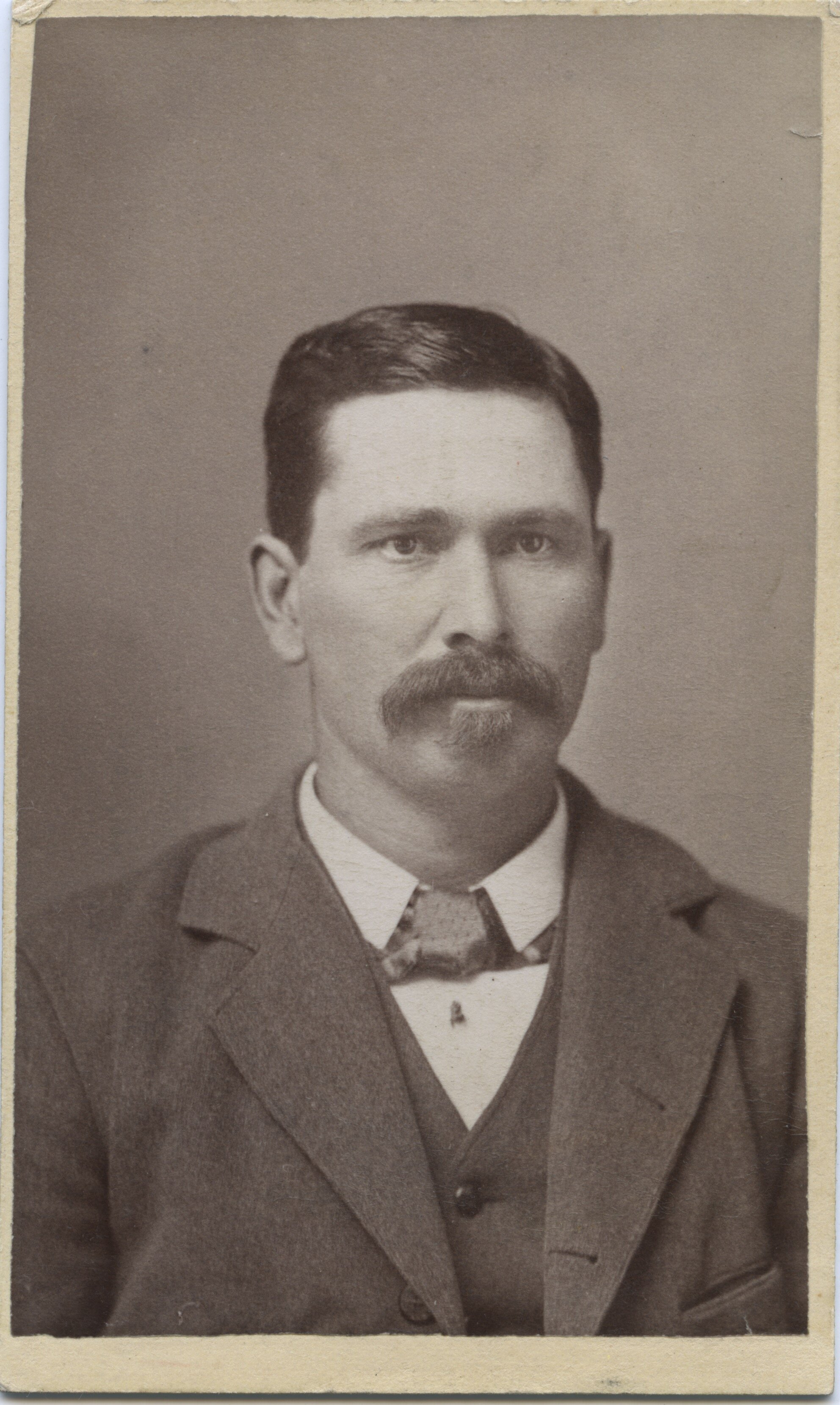

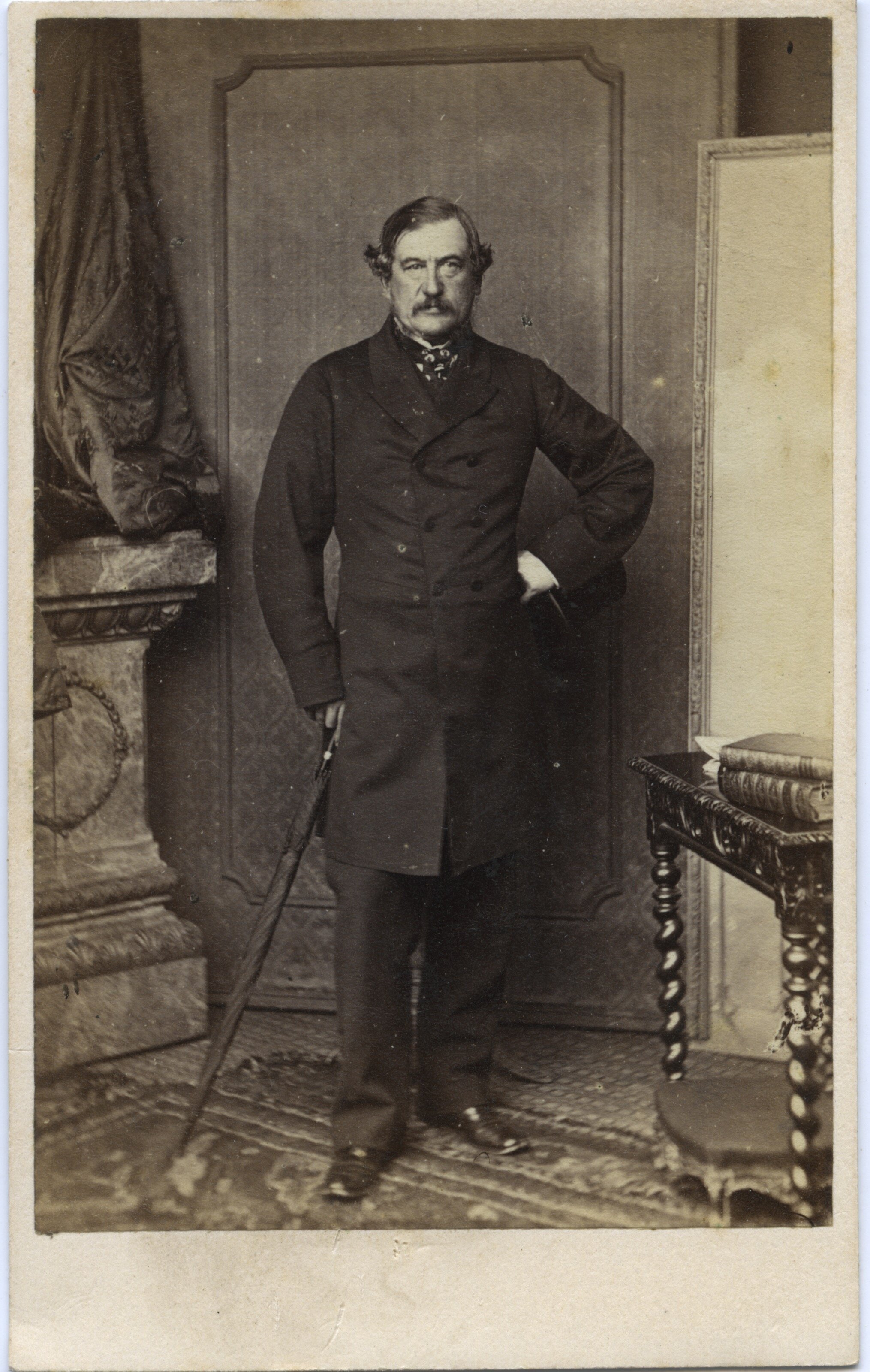

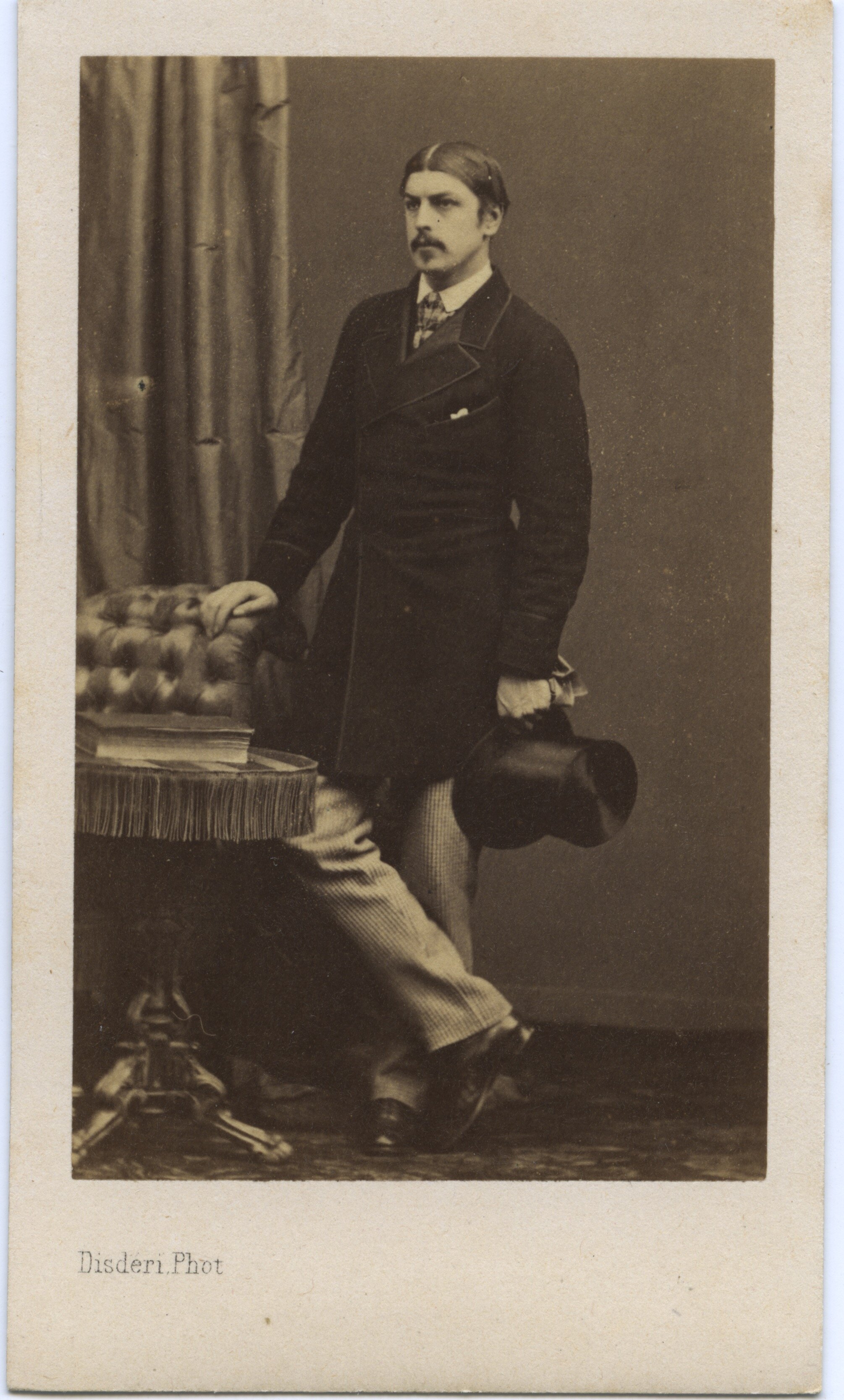

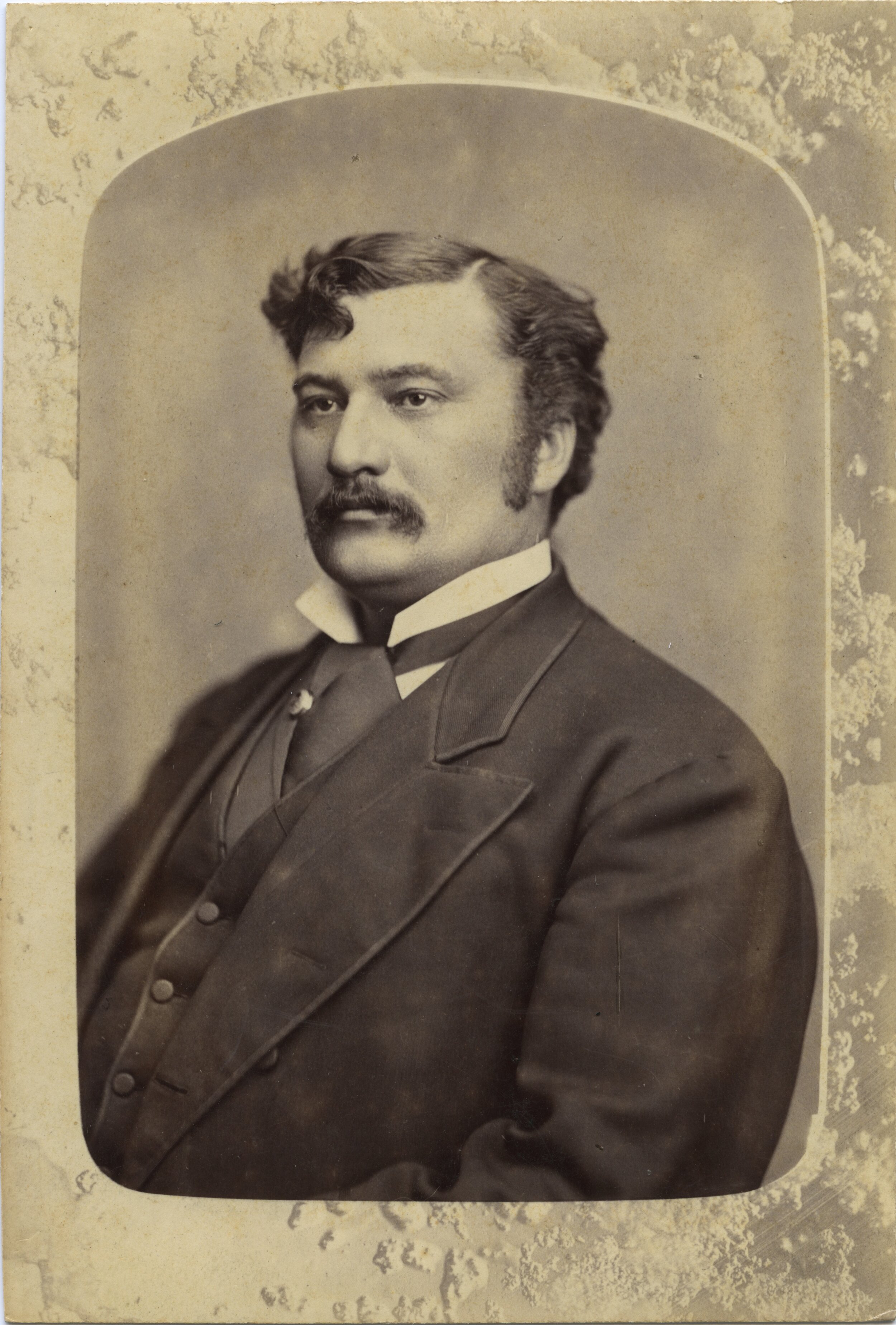

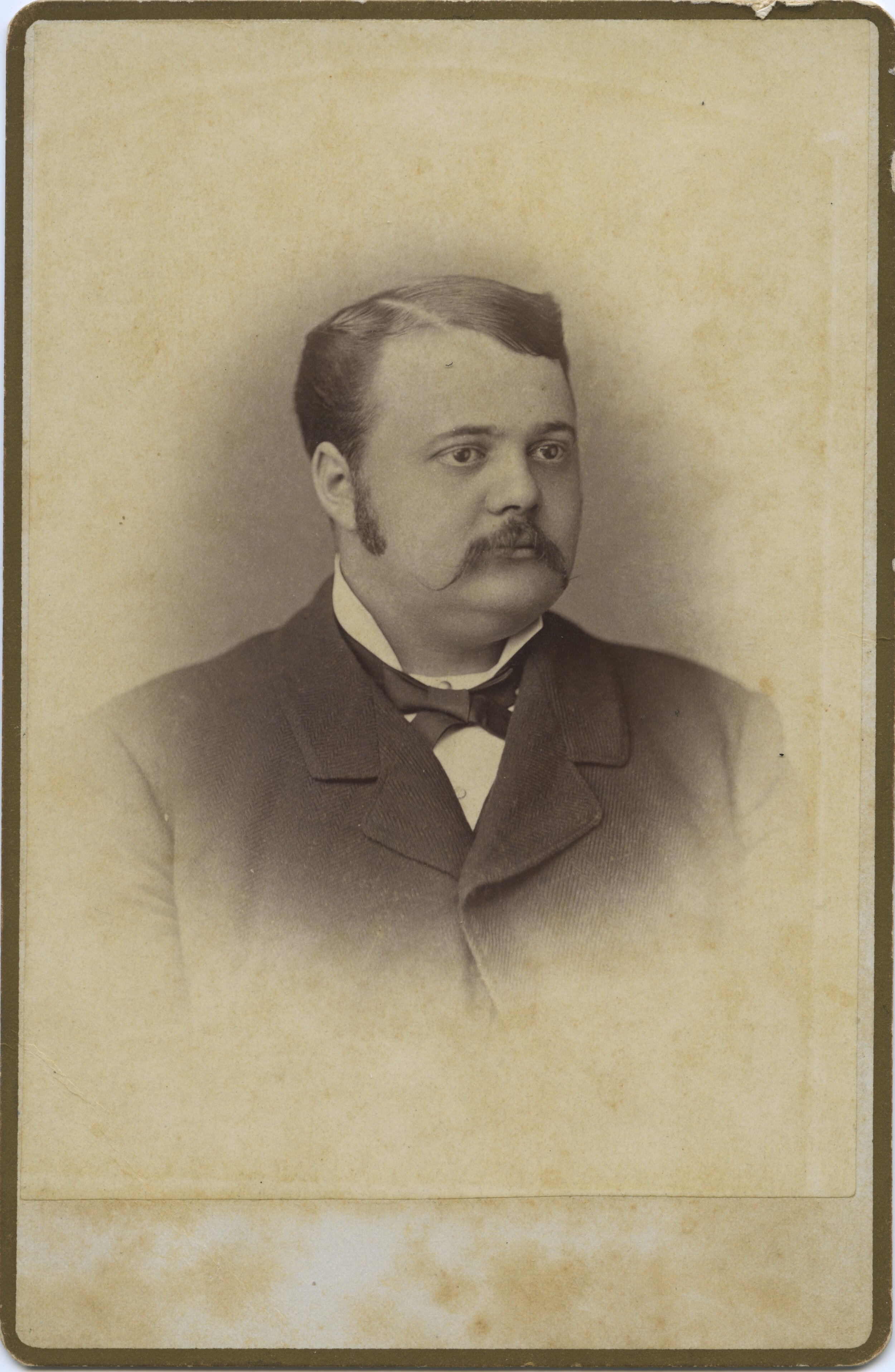

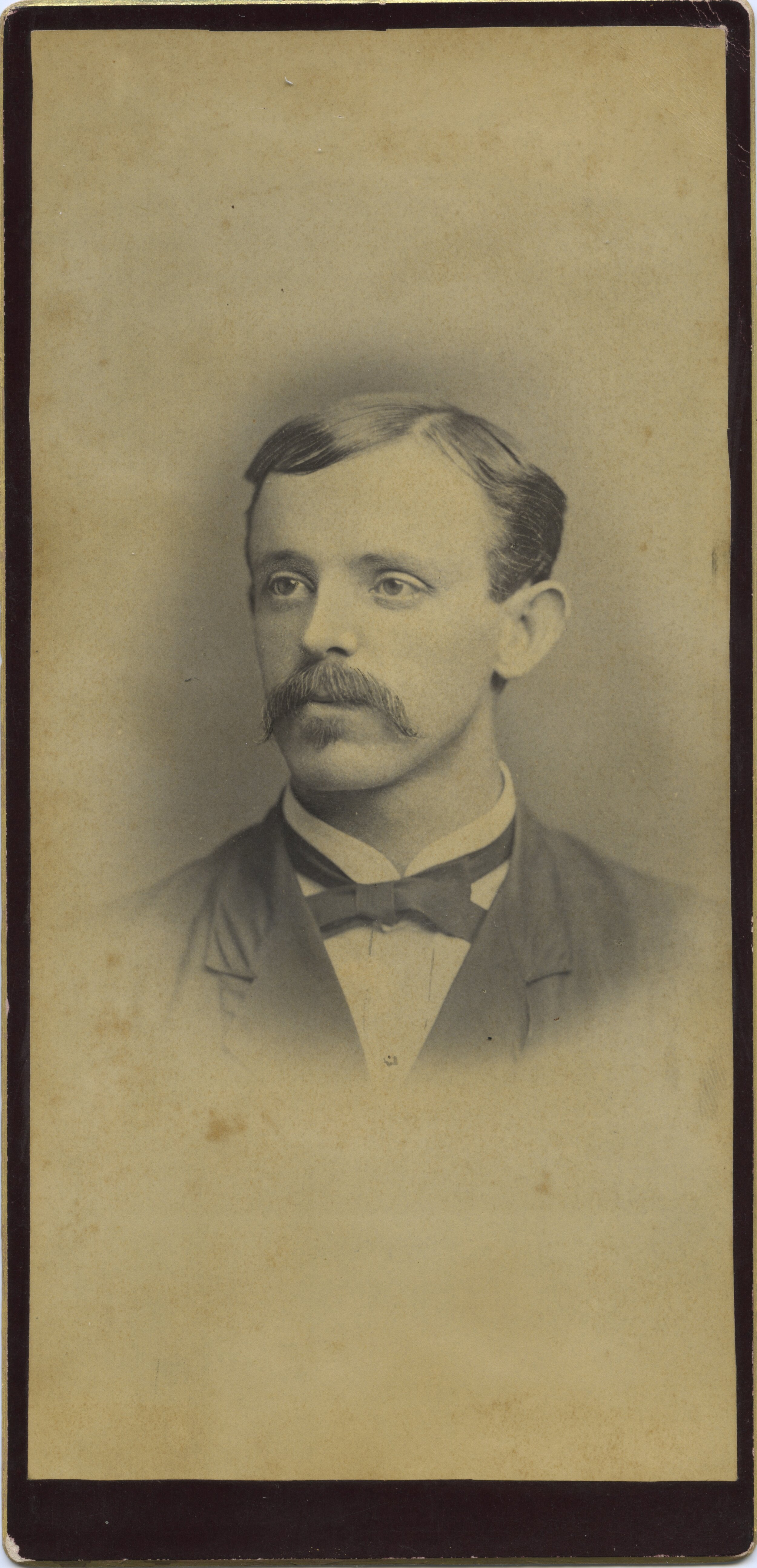

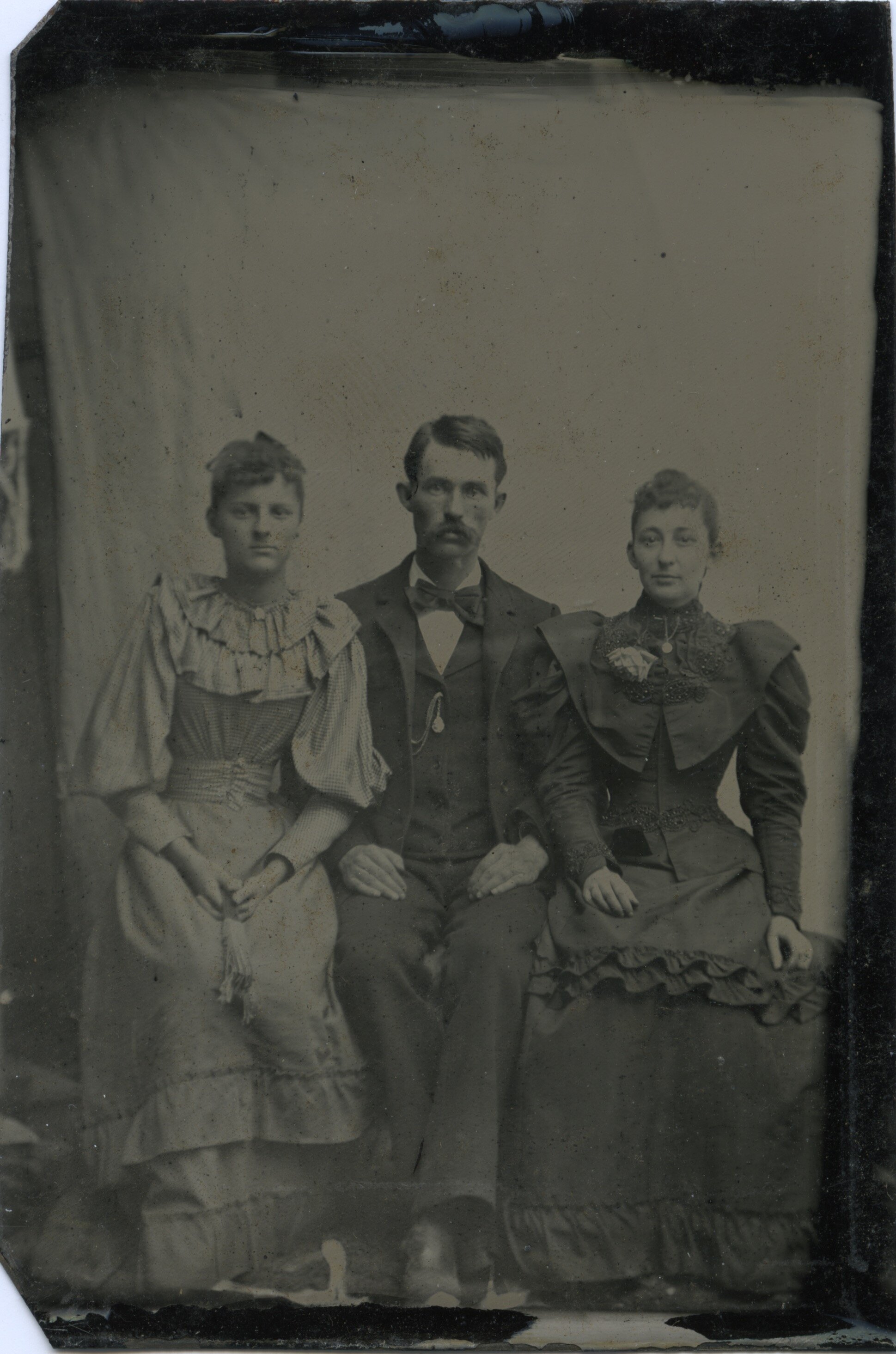

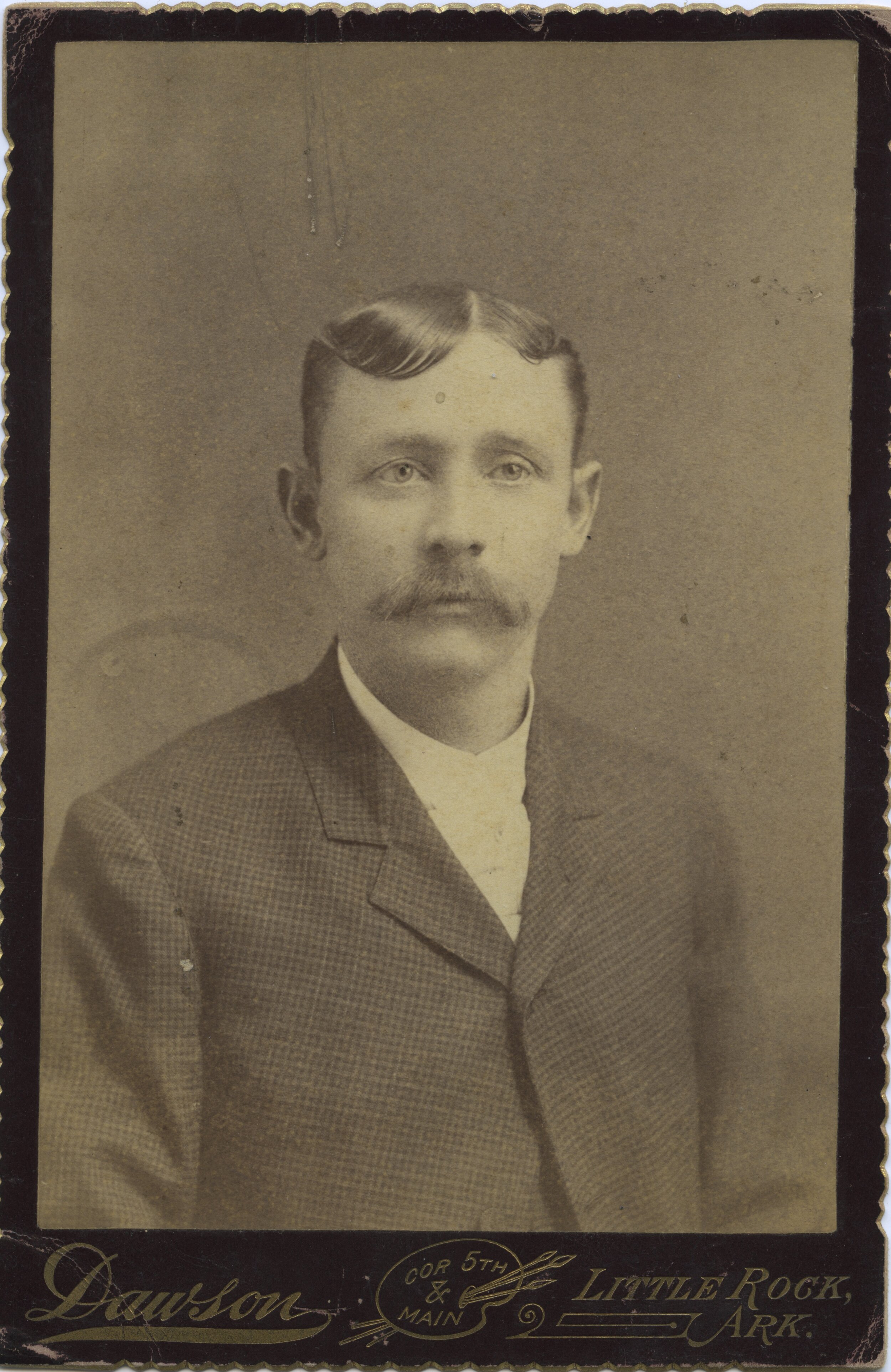

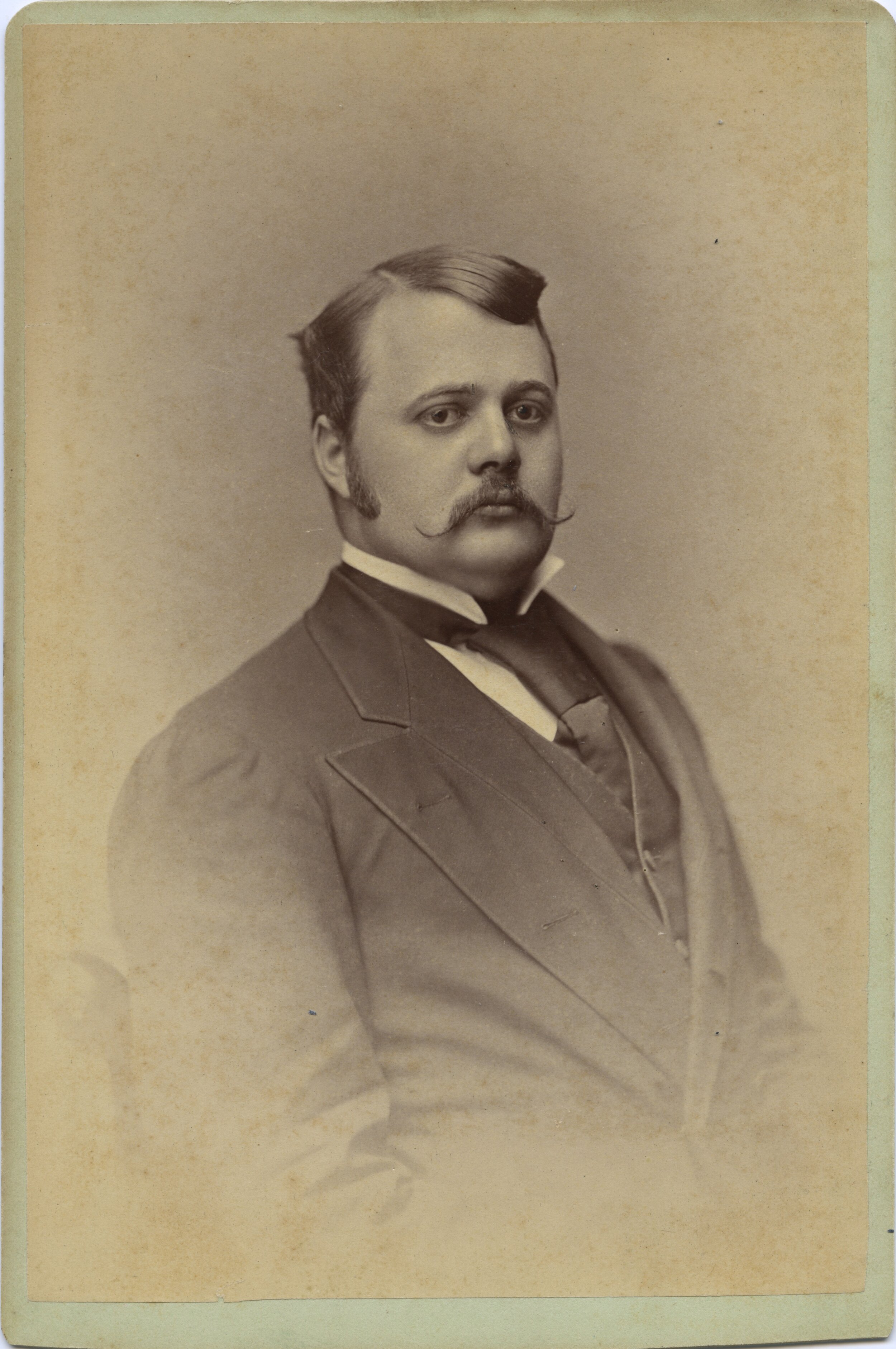

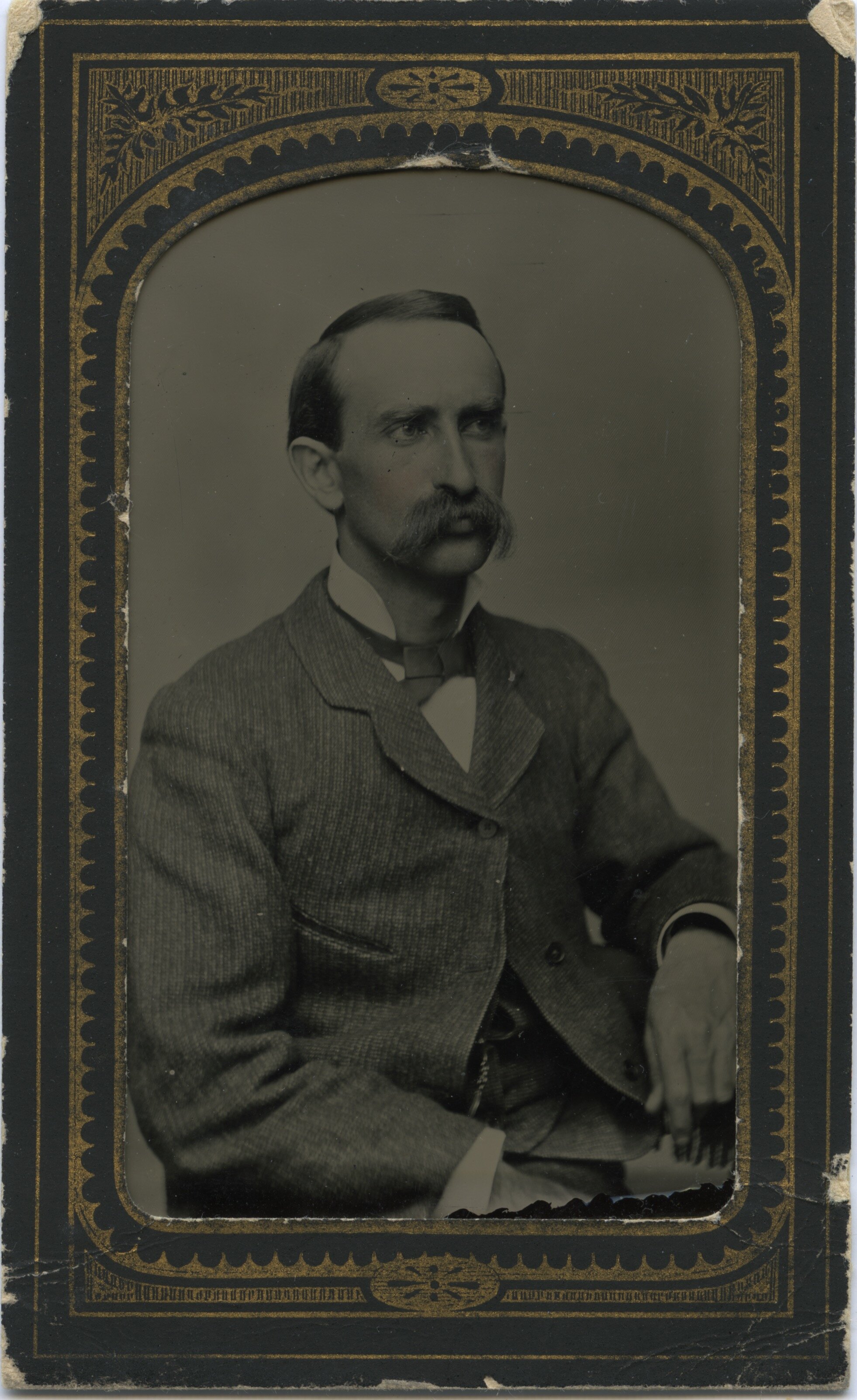

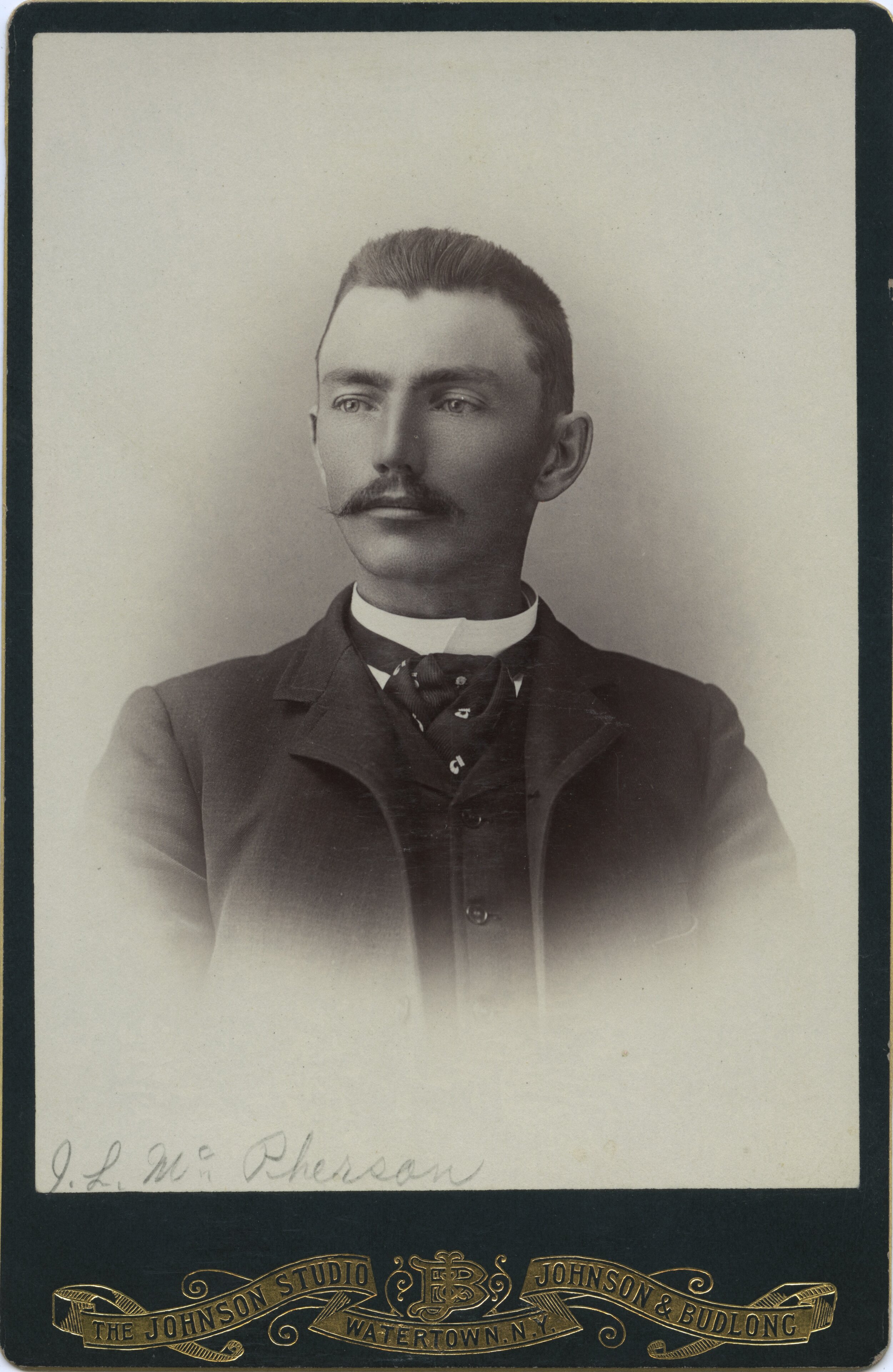

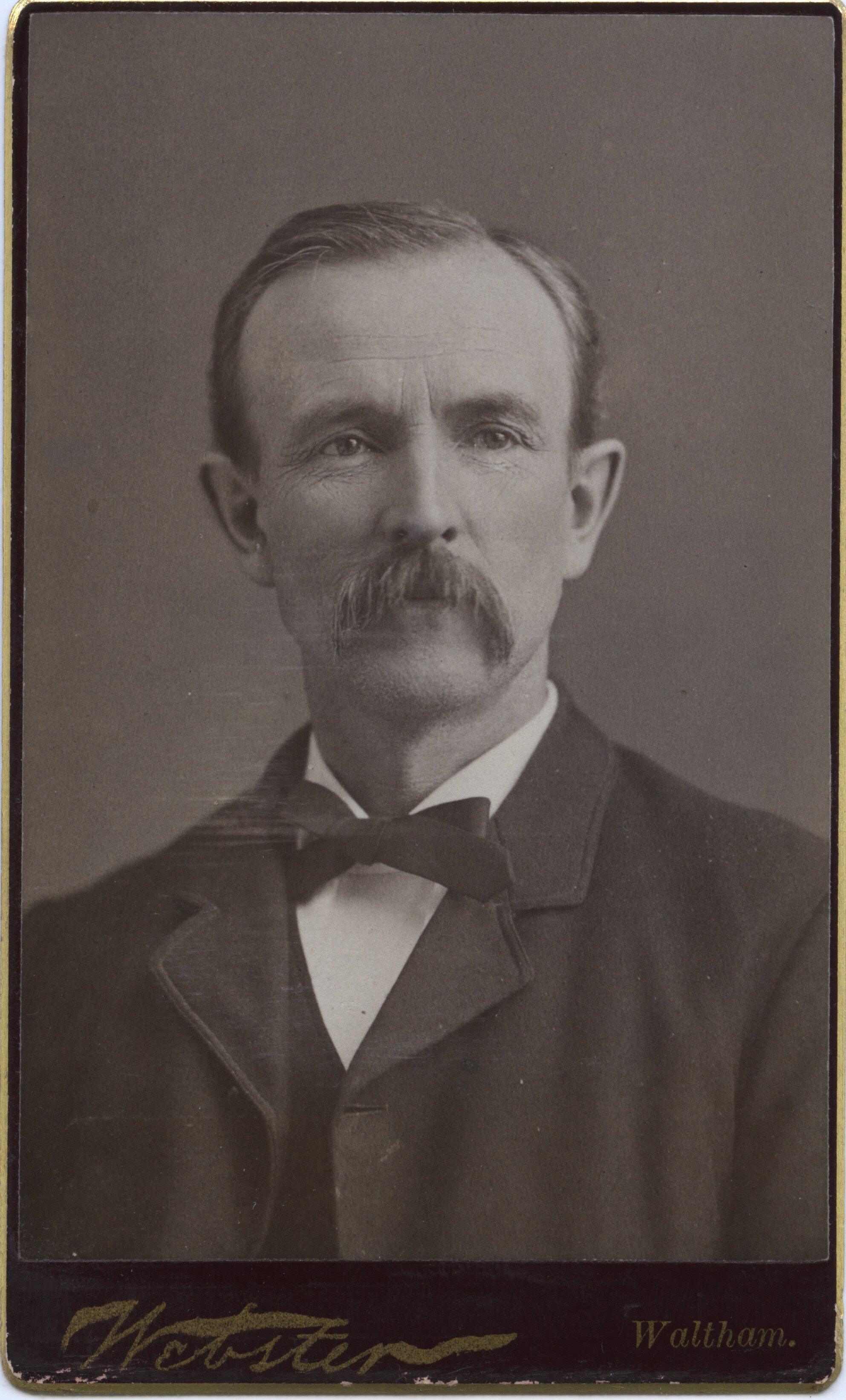

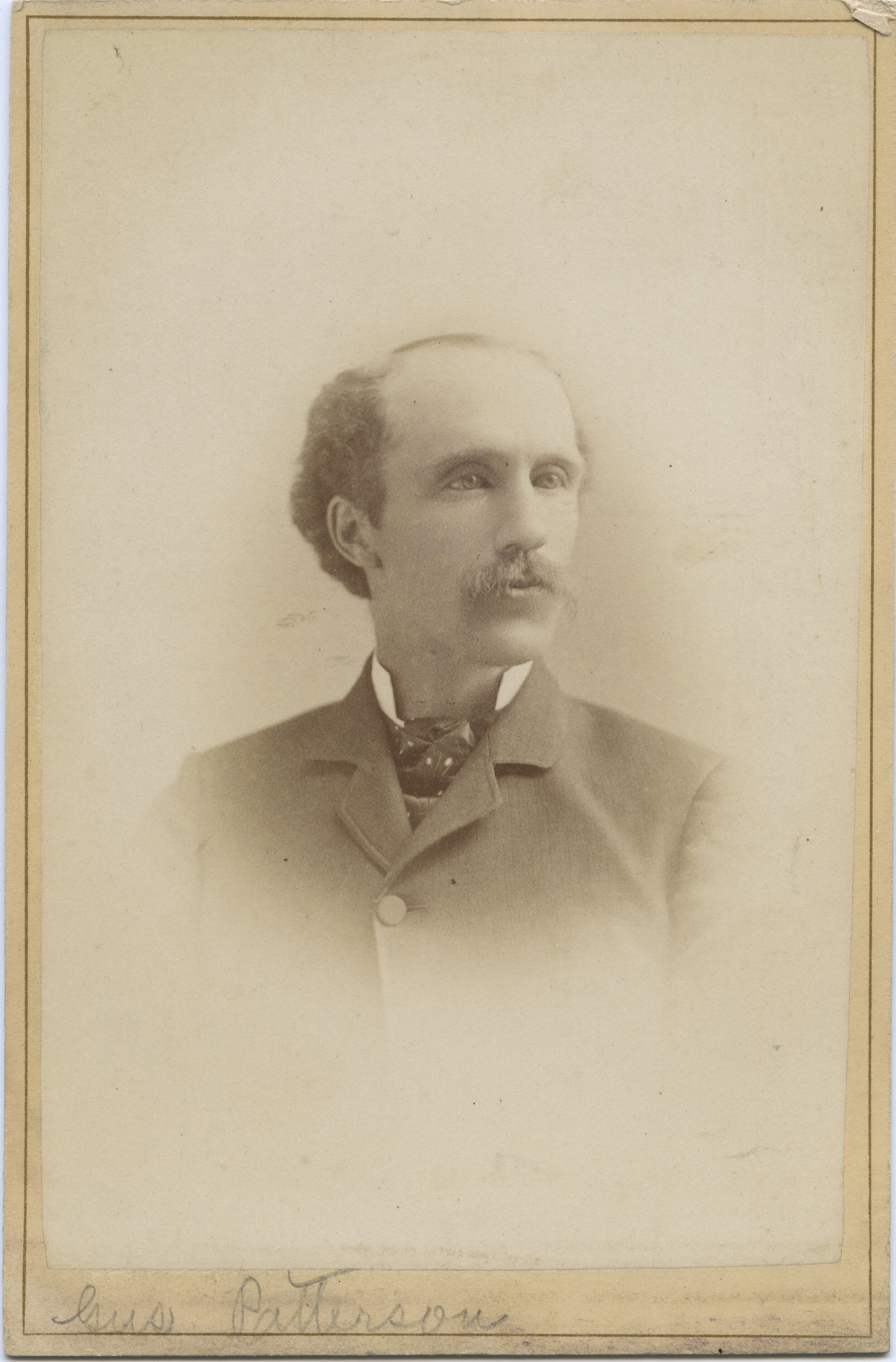

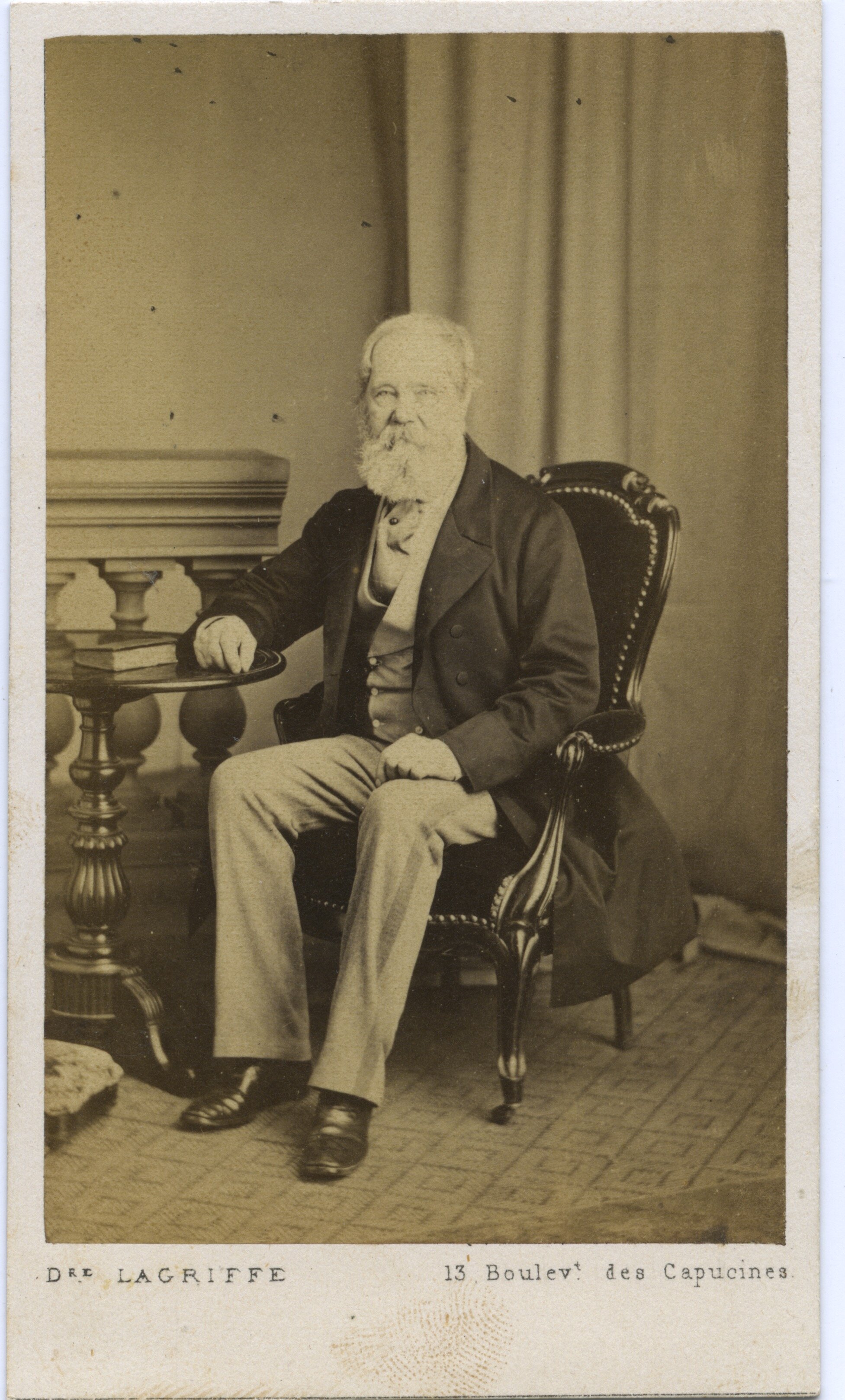

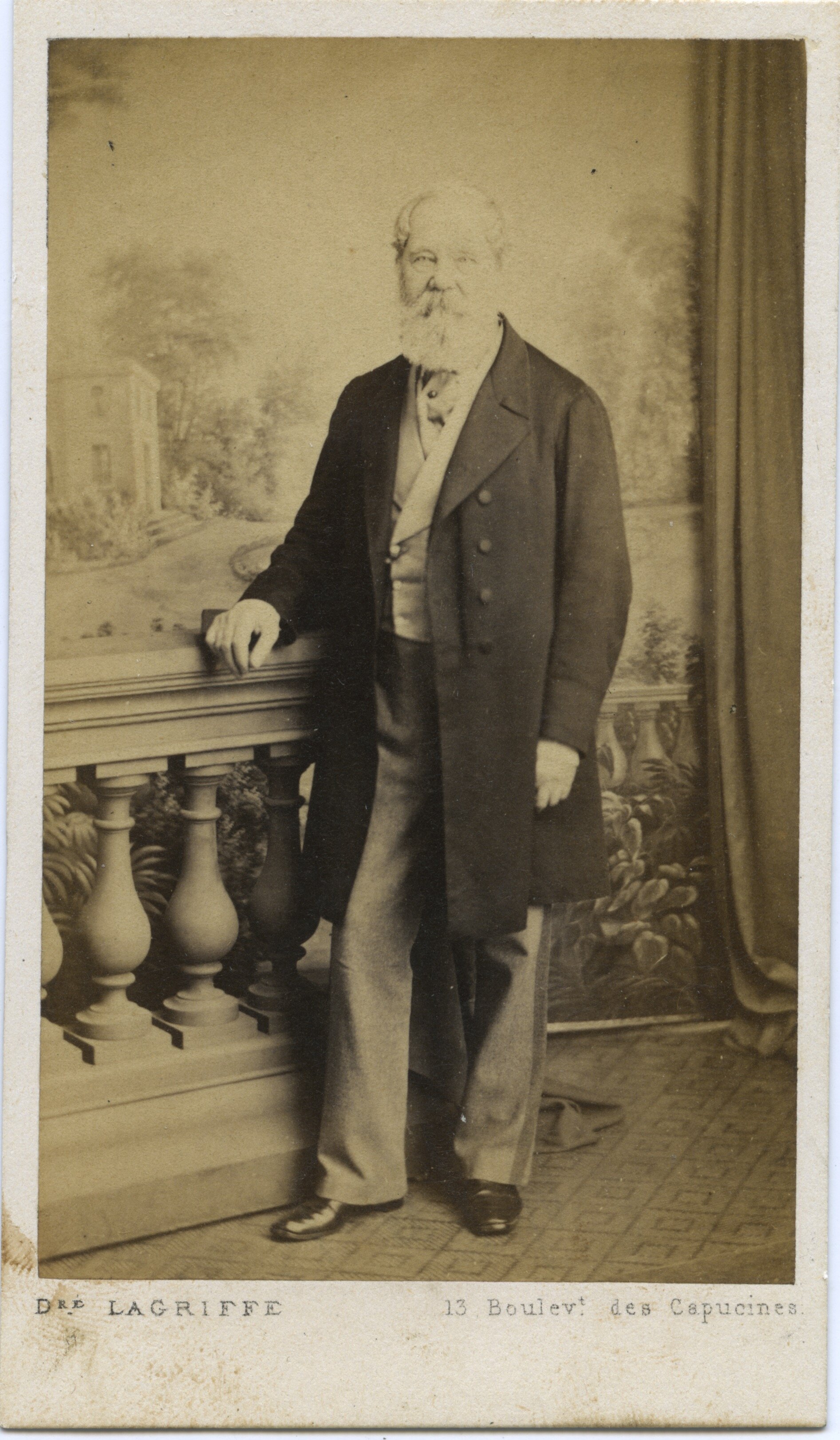

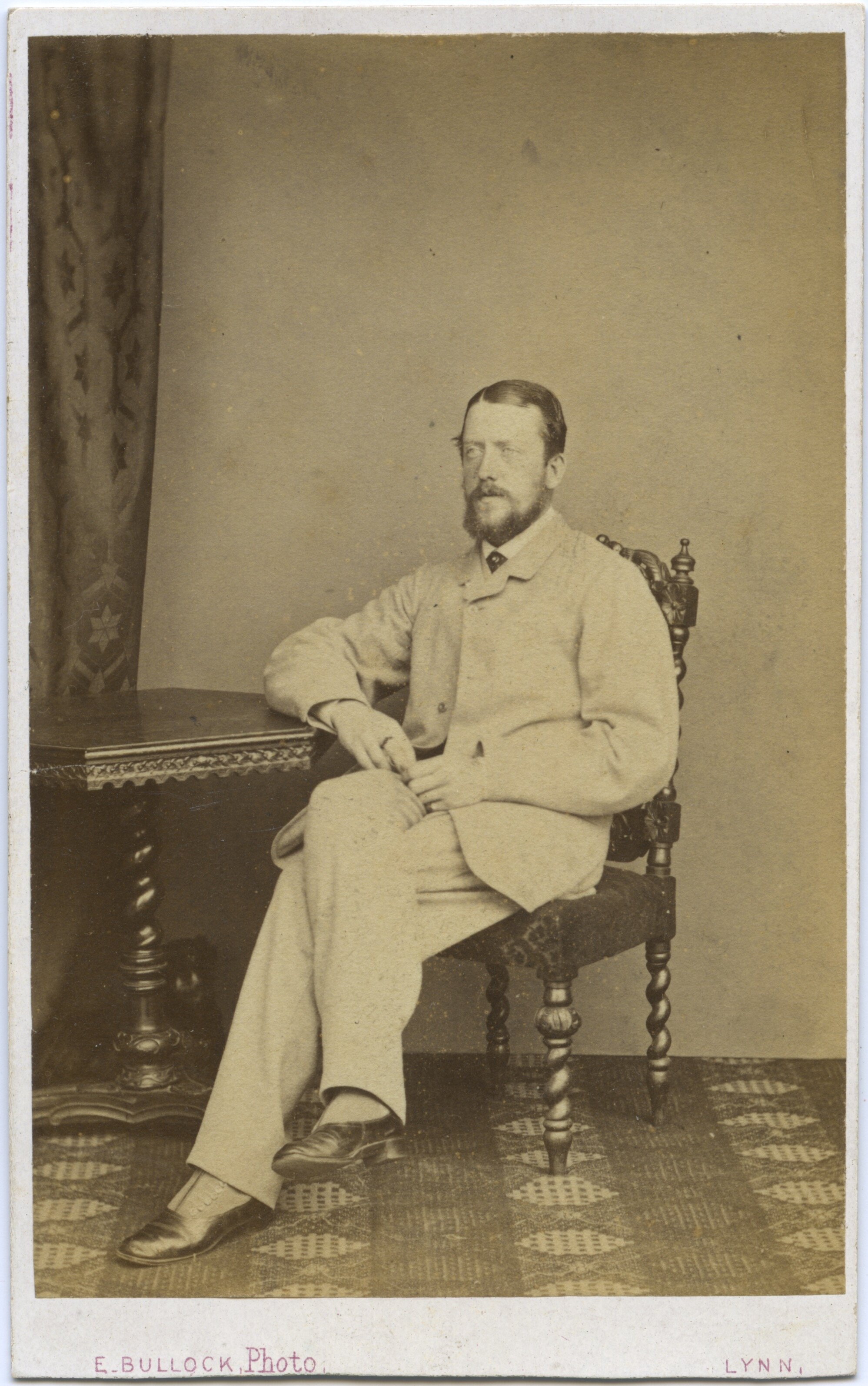

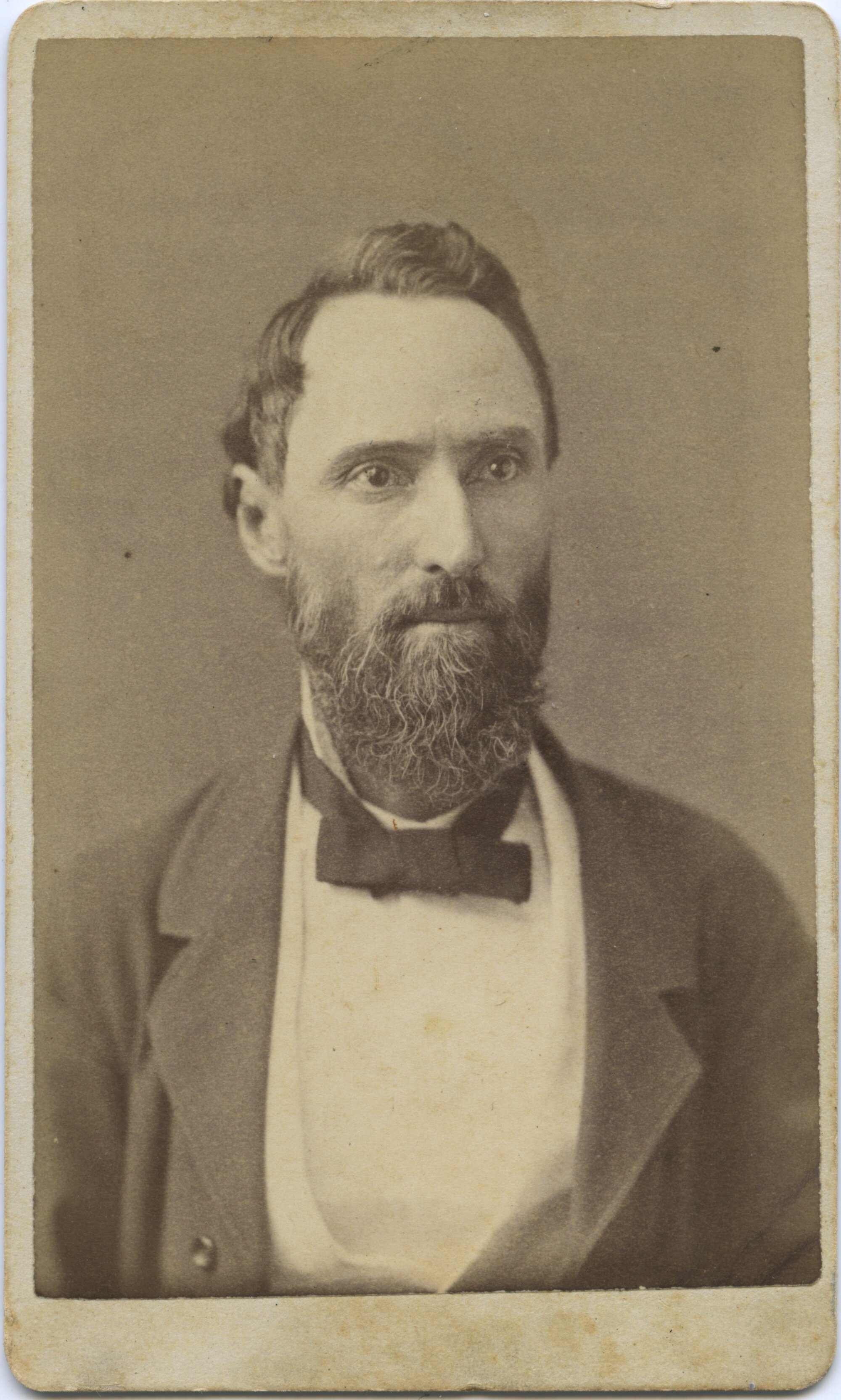

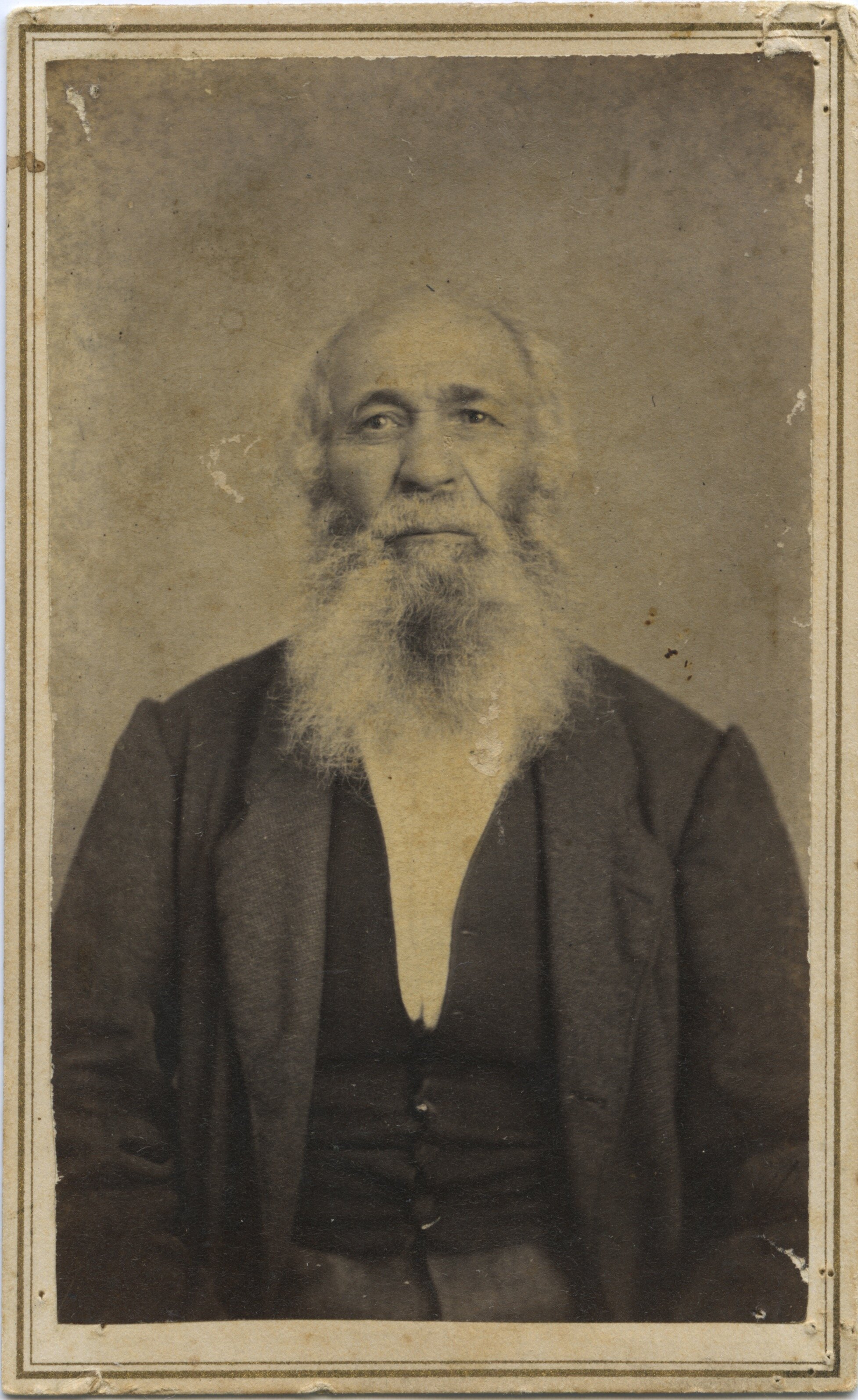

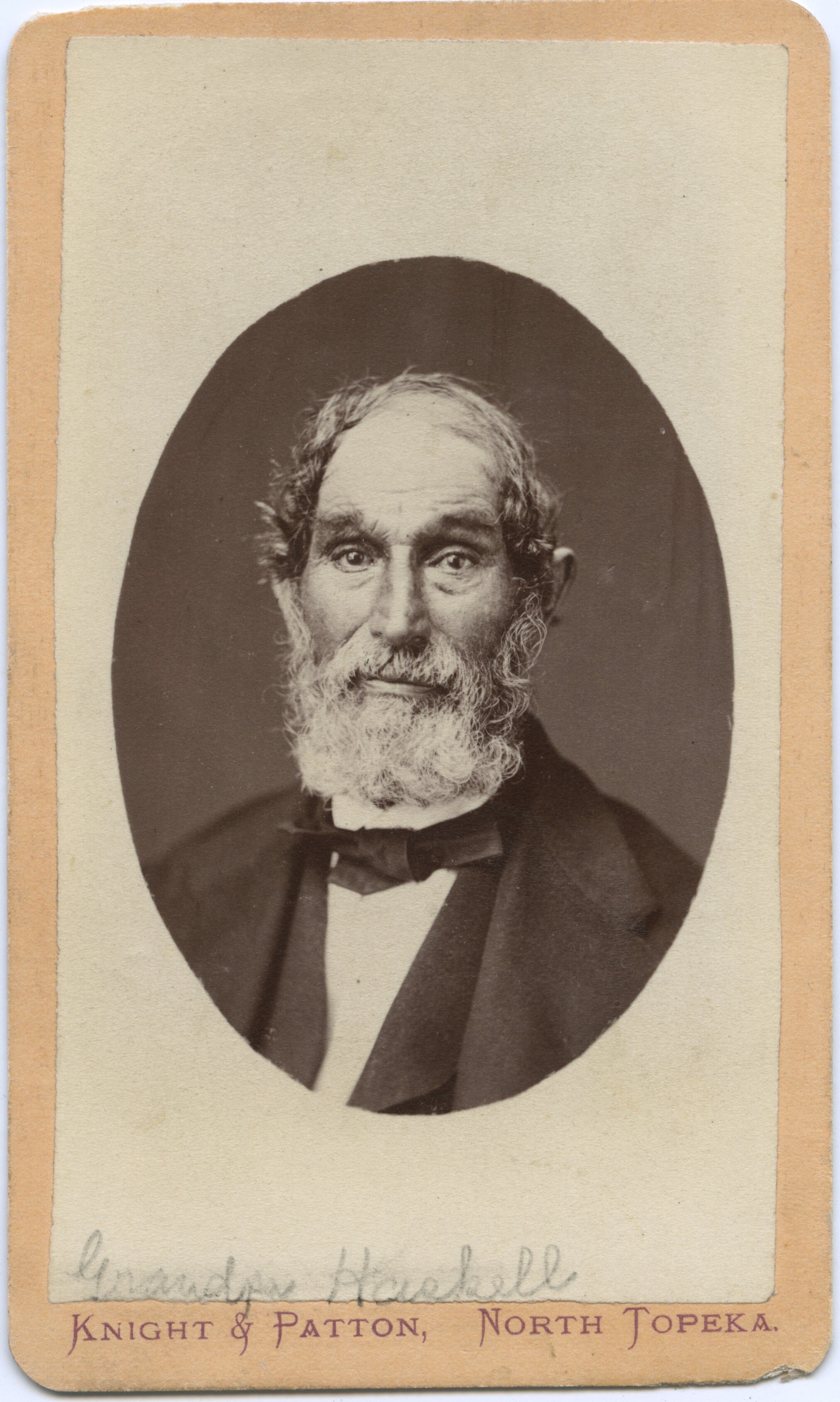

Tags: fashion, History CollectionThe Victorian Era fashion (1837-1901) was a time marked by immense changes in technology and distribution as well as elaborate and creative trends. The mass production of sewing machines in the 1850s and introduction of synthetic dyes in clothing led to more affordable fashions for the middle class. Fashion magazines and distribution also led to the broader distribution of fashionable trends. For women – the Victorian era placed them mostly in domestic roles and their fashion was a representation of their station in society. For men, it seems, facial hair fashions erupted in the late Victorian era as depicted in many of the images on-view at The Grace Museum in the exhibition, Early Photographic Portraits from the Permanent Collection.

Following Prince Albert’s death in 1861, Queen Victoria plunged into mourning and wore black for the rest of her life. Her son, Prince Edward, was heir apparent but given no real political duties. As Prince of Wales, “Bertie” travelled around the world and became known as a playboy and an arbiter of fashion, bringing new styles to popularity.

As times continued to change and new social classes emerged, fashion and proper comportment was of the upmost importance to those climbing up through the middle classes. Displaying wealth through clothing and possessions showed that one had arrived in society. (SOURCE)

What About Whiskers? The forgotten facial hair fashion of 19th-century Britain.

JUNE 21, 2017 ~ DR ALUN WITHEY (SOURCE)

In 1843, an article appeared in the New Orleans ‘Picayune’ newspaper, titled ‘Whiskers. Or, a clean shave’. Dwelling on their utility as ‘ornamental appendages to the human face’, the authors sought to discuss how they contributed to the ‘”masculineness” of manhood’. They even – jokingly – referred to an, as yet undeveloped branch of natural sciences; ‘Whiskerology’.

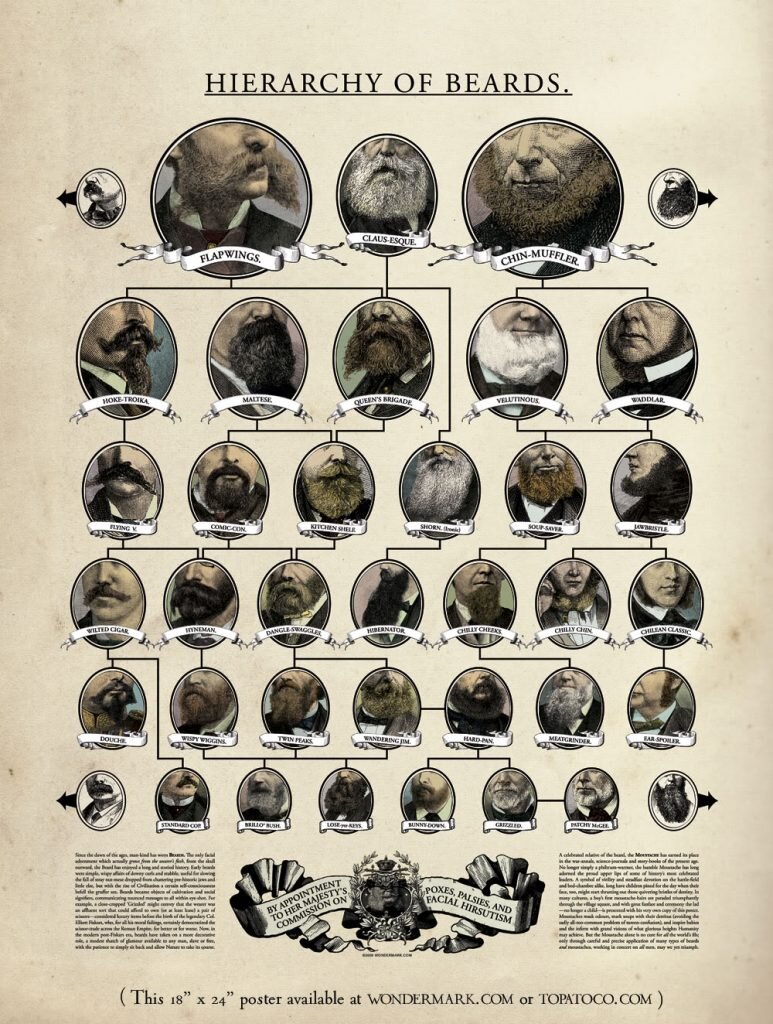

Taking a long view of facial hair fashions since the 17th century, it’s broadly true that beards and moustaches began to decline after around 1680, and disappeared completely through the eighteenth century, until, first the moustache, and then the beard returned with full vigour in the middle of the nineteenth century. So, from bearded, to beardless and back again in around 200 years.

But that’s actually not quite the case. Around the turn of the nineteeth century, male facial hair made what might be regarded as an initial skirmish, before the full frontal facial assault of the 1850s. It was not long-lived; by no means was there a ‘whisker movement’. But, for the first decade of the 19th century, whiskers were definitely a ‘thing’.

There is sometimes confusion about what whiskers actually are, and how they differ from beards. Sometimes the two terms are used interchangeably. Even in contemporary articles whiskers could be used as a catch-all for beards or for beard hairs. But technically they refer to different things. Whilst beards are of the cheeks and chin, whiskers are specific to the sides of the face, and jawline. Also, whilst beards are generally a single entity, whiskers, like moustaches, come as a pair.

The fashion for whiskers seems to have begun quite abruptly around 1800. There were sneering reports, for example, of a new trend amongst young men about town, for cultivating their side -whiskers, and showing them off in public. To a polite society still embracing ideals of neatness and smooth, manly elegance, this was little less than scandalous. The desirability of whiskers, however, was such that the wigmaker Ross of Bishopsgate took to the Times to advertise his new contrivance of a wig with whiskers attached through ‘such remarkable adhesion as cannot be discovered from Nature itself’. This ‘new invented whisker’ could be combed to suit any fashion, but came at the high price of three pounds and three shillings – a full pound dearer than his standard, un-whiskered peruke.

By 1808, so popular had whiskers become, that even women were apparently trying to get in on the act. Several fashion journals (such as the popular ‘Le Belle Epoque’) reported a coming trend for ladies to train their lovelocks down the side of their faces ‘in imitation of whiskers’. For some this was a step too far. ‘I am at a loss to conceive what a gentleman will be pleased with in a lady’s whiskers’. Nonetheless, this was clearly a popular fashion. Whether it was ‘The Countess Dowager of B—s whiskers’ which were apparently ‘already in great forwardness’, or the ‘belles of Cockermouth’, a set of whiskers was seriously a la mode. At one stage it was suggested that an enterprising perfumer was even selling preparations ‘To Ladies of Fashion ‘who have tried various preparations for changing the hair, whiskers and eyebrows, without success’, but this proved to be an error of phrasing, as the Satirist magazine were happy to poke fun at!

There were certainly products aimed specifically at cultivating whiskers though. By 1808, ‘Prince’s Russia Oil’ and ‘Macassar Oil’ were in demand, and advertisers claimed that they were specifically designed to ‘promote whiskers’ and prevent damage or discolouration caused by frequent wetting.

By 1808, so popular had whiskers become, that even women were apparently trying to get in on the act. Several fashion journals (such as the popular ‘Le Belle Epoque’) reported a coming trend for ladies to train their lovelocks down the side of their faces ‘in imitation of whiskers’. For some this was a step too far. ‘I am at a loss to conceive what a gentleman will be pleased with in a lady’s whiskers’. Nonetheless, this was clearly a popular fashion. Whether it was ‘The Countess Dowager of B—s whiskers’ which were apparently ‘already in great forwardness’, or the ‘belles of Cockermouth’, a set of whiskers was seriously a la mode. At one stage it was suggested that an enterprising perfumer was even selling preparations ‘To Ladies of Fashion ‘who have tried various preparations for changing the hair, whiskers and eyebrows, without success’, but this proved to be an error of phrasing, as the Satirist magazine were happy to poke fun at!

There were certainly products aimed specifically at cultivating whiskers though. By 1808, ‘Prince’s Russia Oil’ and ‘Macassar Oil’ were in demand, and advertisers claimed that they were specifically designed to ‘promote whiskers’ and prevent damage or discolouration caused by frequent wetting.

By 1808, so popular had whiskers become, that even women were apparently trying to get in on the act. Several fashion journals (such as the popular ‘Le Belle Epoque’) reported a coming trend for ladies to train their lovelocks down the side of their faces ‘in imitation of whiskers’. For some this was a step too far. ‘I am at a loss to conceive what a gentleman will be pleased with in a lady’s whiskers’. Nonetheless, this was clearly a popular fashion. Whether it was ‘The Countess Dowager of B—s whiskers’ which were apparently ‘already in great forwardness’, or the ‘belles of Cockermouth’, a set of whiskers was seriously a la mode. At one stage it was suggested that an enterprising perfumer was even selling preparations ‘To Ladies of Fashion ‘who have tried various preparations for changing the hair, whiskers and eyebrows, without success’, but this proved to be an error of phrasing, as the Satirist magazine were happy to poke fun at!

There were certainly products aimed specifically at cultivating whiskers though. By 1808, ‘Prince’s Russia Oil’ and ‘Macassar Oil’ were in demand, and advertisers claimed that they were specifically designed to ‘promote whiskers’ and prevent damage or discolouration caused by frequent wetting.

By 1808, so popular had whiskers become, that even women were apparently trying to get in on the act. Several fashion journals (such as the popular ‘Le Belle Epoque’) reported a coming trend for ladies to train their lovelocks down the side of their faces ‘in imitation of whiskers’. For some this was a step too far. ‘I am at a loss to conceive what a gentleman will be pleased with in a lady’s whiskers’. Nonetheless, this was clearly a popular fashion. Whether it was ‘The Countess Dowager of B—s whiskers’ which were apparently ‘already in great forwardness’, or the ‘belles of Cockermouth’, a set of whiskers was seriously a la mode. At one stage it was suggested that an enterprising perfumer was even selling preparations ‘To Ladies of Fashion ‘who have tried various preparations for changing the hair, whiskers and eyebrows, without success’, but this proved to be an error of phrasing, as the Satirist magazine were happy to poke fun at!

There were certainly products aimed specifically at cultivating whiskers though. By 1808, ‘Prince’s Russia Oil’ and ‘Macassar Oil’ were in demand, and advertisers claimed that they were specifically designed to ‘promote whiskers’ and prevent damage or discolouration caused by frequent wetting.

Some of the arguments made for whiskers during this period were also in fact remarkably similar to those later made for beards. Echoing later claims for the innate masculinity of beards, whiskers were said to be ‘grave and manly’. Whiskers had been venerated by ‘the ancients’, lending them an air of authority and wisdom. It was, as one commentator noted, ‘silly to oppose so ancient a custom in an age so attached to antiquity’. Moreover, the ‘cruelty of shaving’ was matched by the dangers of the shaking hands of ‘unskilled operators’ (barbers). Most of all, it was argued, whiskers were beautiful, especially when set against the ‘unfringed faces of the present day’.

At the same time whiskers were beginning to be held up as a desirable characteristic of the male face. A man obtaining goods under false pretences was described in 1811 as of ‘gentlemanly appearance’, and of ‘handsome countenance, who wears black whiskers’. A report of the suicide of Royal Footman Andrew Tranter in 1810 noted his reputation for ‘neatness and cleanliness’ in his dress and appearance, and that he ‘wore very large whiskers and was considered a handsome young man’. Such seemingly innocuous reports in fact hides an important transition; after more than a century, facial hair was again aesthetically and socially pleasing but, more than this, cleanly.

In 1813, ‘The Spirit of Public Journals’ reported the ‘Growing custom of encouraging whiskers’ and the barbed criticisms levelled at them by critics. It was apparently even suggested that an Act of Parliament should be made to curtail the fashion. Even then, the subject of male facial hair was contentious! Fortunately, the author argued, the ‘Whiskerandos’ outnumbered their tormentors and merely increased in proportion to the opposition levelled against them.

Despite the ‘Spirit’s enthusiasm, however, it seems that the fashion for side-whiskers had abated by the end of the 1810s. It’s not clear why it declined; perhaps Victorian society was not quite ready for the hirsute revolution of the mid century. But it is interesting to consider whiskers, not only as a sort of trial run for what came later, but also as an often-forgotten element in men’s facial hair fashions. It wasn’t all beards and moustaches.

As the current beard style continues to change, at the moment with beards seemingly getting smaller and more closely trimmed, will we see the return of such fantastic styles as the ‘Dundreary’ whiskers or (please no!) the ‘chin curtain’? Perhaps the Whiskerandos will rise again. If they do, you can be sure that this particular ‘Whiskerologist’ will be there to document it.

In 1813, ‘The Spirit of Public Journals’ reported the ‘Growing custom of encouraging whiskers’ and the barbed criticisms levelled at them by critics. It was apparently even suggested that an Act of Parliament should be made to curtail the fashion. Even then, the subject of male facial hair was contentious! Fortunately, the author argued, the ‘Whiskerandos’ outnumbered their tormentors and merely increased in proportion to the opposition levelled against them.

Despite the ‘Spirit’s enthusiasm, however, it seems that the fashion for side-whiskers had abated by the end of the 1810s. It’s not clear why it declined; perhaps Victorian society was not quite ready for the hirsute revolution of the mid century. But it is interesting to consider whiskers, not only as a sort of trial run for what came later, but also as an often-forgotten element in men’s facial hair fashions. It wasn’t all beards and moustaches.

As the current beard style continues to change, at the moment with beards seemingly getting smaller and more closely trimmed, will we see the return of such fantastic styles as the ‘Dundreary’ whiskers or (please no!) the ‘chin curtain’? Perhaps the Whiskerandos will rise again. If they do, you can be sure that this particular ‘Whiskerologist’ will be there to document it.