Texas Regionalism Revisited

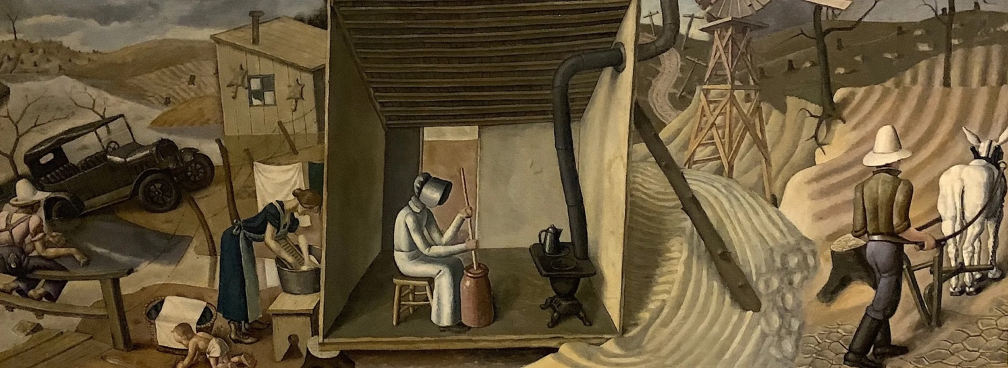

“In the 1930s, a group of young artists—including Jerry Bywaters, Alexandre Hogue, William Lester, Thomas Stell, Harry Carnohan, and Coreen Spellman, among others—gained national recognition for their scenic and ideological interpretations of the local environment. Although they depicted the people and landscapes of Texas in identifiable and representational manners, each artist possessed their own style, often combining realism with modernist influences ranging from Cubism to Surrealism creating evocative paintings to provide a poignant glimpse of life and art in Texas during the era of the Great Depression.”

Cummins, Light Townsend. “Regionalism: Texas History is Southwestern History.” Southwestern Historical Quarterly, vol. 125 no. 4, 2022, p. 394-407. Project MUSE, https://doi.org/10.1353/swh.2022.0028.

This exhibition will include iconic Texas Regionalist artwork by Charles Taylor Bowling, Jerry Bywaters, Harry Carnohan, John Douglass, Otis Dozier, Edward Eisenlohr, Alexander Hogue, Merritt Mauzey, Florence McClung, H.O. Robertson, Everett Spruce, and Thomas M. Stell, Jr., on loan from private collections and from The Grace Museum’s permanent collection.

The Texas Regionalist artists featured in this exhibition were born in rural areas of Texas and the Southwest in the late 19th or the early years of the 20th century. They pursued artistic careers during the Great Depression; an unlikely time for success in areas where widespread drought scarred the rural landscape and poverty drove people from their homes. The highly sophisticated art of the Texas Regionalists rejected European trends in favor of expressive works of art focusing on the places they knew and experienced. Today, artwork by Texas Regionalists, completed almost a century ago, reveals the concerns of artists as individuals in difficult circumstances as well as our understanding of the popular term, a sense of place.

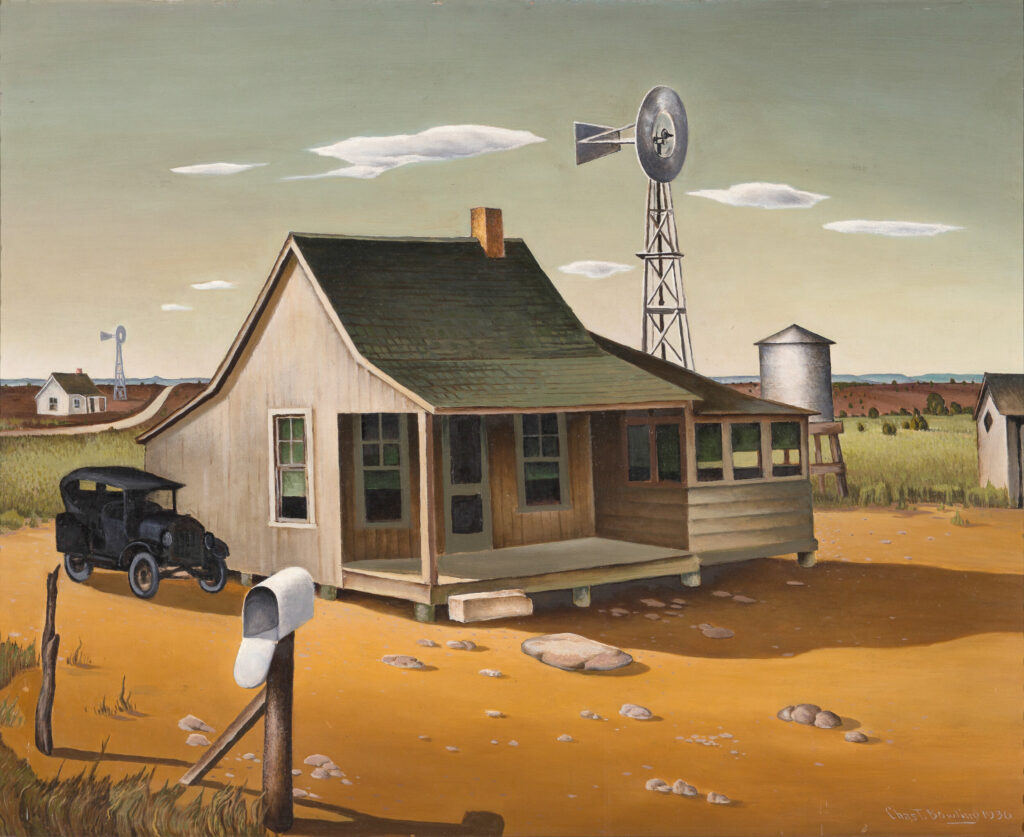

Taking a closer look at the paintings on view, it is noticeable that many of the celebrated Texas Regionalists, while committed to their sense of place, were also incorporating subtle modernist distortions of scale, composition, and viewpoints in a radical formal experiment to create drama, mystery and emotional impact. Thomas Stell, Jr. achieves a dramatic integration of realism and multiple points of view in Texas Mural, 1937. Everett Spruce doesn’t tell us exactly what happened in West Texas Incident, 1937. Charles Bowling doesn’t reveal where the residents have gone, why the Model T appears too small, or why the mailbox is empty in Texas Landscape, 1936. Is Jerry Bywaters pleased with the new residential development in Texas Subdivision 1938? Are the Neighbors viewed from above in Alexandre Hogue’s 1934 painting unaffected by the Great Depression? These works of art remain relevant because Texas Regionalism is a unique and important chapter in the evolution of Texas and American art, when artists in the state artistically expanded reality, not only to record a time and place, but to create arresting affirmations of a lived experience.