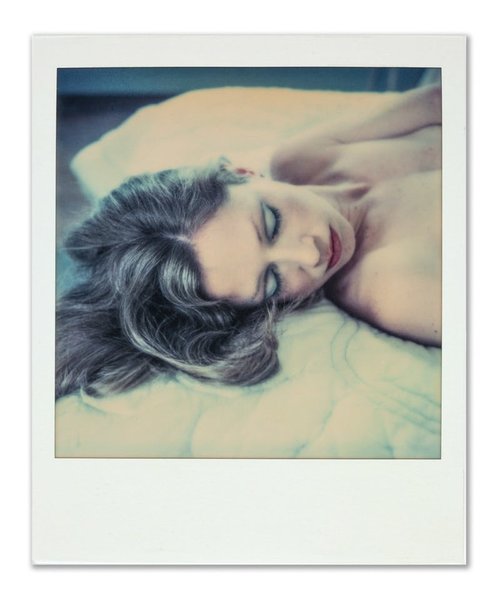

Paul Black: Carol

Photographer Paul James Black presents an intimate group of Polaroids and black and white photographs of only one person; his wife Carol. The photographs in the exhibition, Paul Black: Carol, were taken in the first two decades of their marriage and offer an intimate record into their private world in the 1960s and 70s. Carol is the only subject in this chronicle. With disappearance of the family photo album in the current digital selfie age, Black’s photographs are a reminder of the value of physical documentation of a life over time.

This poignant series of photographs evolved as the artist’s MFA final project after a fire in his studio destroyed his paintings created for his graduate thesis at Penn State. After teaching art in Pennsylvania he began a career with Polaroid and eventually moved to Dallas to open Photographique, a film lab in Deep Ellum offering traditional photographic services such as developing film, restoring damaged photos, producing prints, and renting out a darkroom to eager photographers.

Part of the HUMAN INTEREST contemporary portraits series of exhibitions.

Five exhibitions examine contemporary interpretations of the enduring tradition of portraiture. Can a portrait be more than a recognizable image of the sitter? Since the advent of photography, the genre of contemporary portraiture has expanded far beyond the requirement of recording a likeness for posterity. Today we expect more than a likeness and we rely on the artist’s skill and creativity to see the subject’s outward appearance in the context of a larger reality. Artists, both traditional and conceptual, continue to draw on the genre’s rich and limitless options for new means of creative expression, and their efforts have been rewarded with a resurgence of critical interest. The artist’s challenge is to apply his or her ingenuity and empathetic insight to illuminate not just a person’s unique appearance, but also engage the viewer. Portrait artists frequently describe their efforts as “collaborative,” recognizing that the process requires both the resemblance of the subject and the intention of the artist. The individual pictured, known or unknown, in a work of art is almost always read by the viewer as an extension of the human experience. How we react is literally in the hands of the artist.

Exhibitions Sponsors