Illustrated Happy Hour: History of Hand Fan

Tags: fashion, History Collection, Illustrated Happy HourHISTORY OF THE HAND FAN IS LONG AND COLORFUL

Country Home magazine

CHICAGO TRIBUNE

July 5, 1987

Stir the air with an antique fan and awaken the silent spirits of centuries.

On the breeze comes a succession of characters as varied as Egyptian pharaohs and jazz-age flappers, Renaissance queens and cockney flower girls. All counted fans among their most prized possessions–from showy arrays of ostrich plumes to webs of silk as fragile as a butterfly’s wing.

According to Country Home magazine, the earliest fans were probably used to quicken the burning of a fire or to keep bothersome insects at bay, but they eventually took on a prestigious role. For centuries, large, long-handled fans were ceremonial symbols of power, the privilege of pharaohs, priests and kings. Even today, fans of this type are carried in formal papal processions.

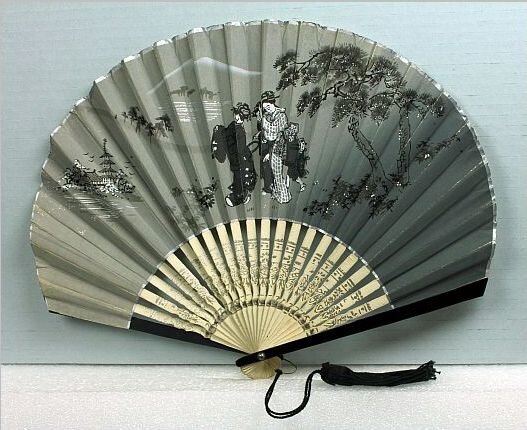

Folding fans are thought to have originated in [Asia] between the 7th and 10th Centuries, and it was there they first became a part of daily life. These fans, as well as the European fans they eventually inspired, were of two types.

Pleated fans have a leaf (or mount) of pleated fabric, paper or leather. The leaf is supported on a series of sticks that are joined at one end by a rivet. Guards, which are the two end sticks, protect the fan when it is closed.

Brise fans are folding fans that have no leaf. The sticks themselves widen toward their outer ends and overlap to form the body of a fan. To hold the fan together, the sticks are artfully strung with ribbon or string. Cockade fans are folding fans of either the pleated or brise type that open to a full circle.

Fan making was an art in China and Japan by the time the first European ships reached the Orient in the early 1500s. Along with other riches unfamiliar to Europeans, Portuguese sailors brought back fans to the markets of Europe.

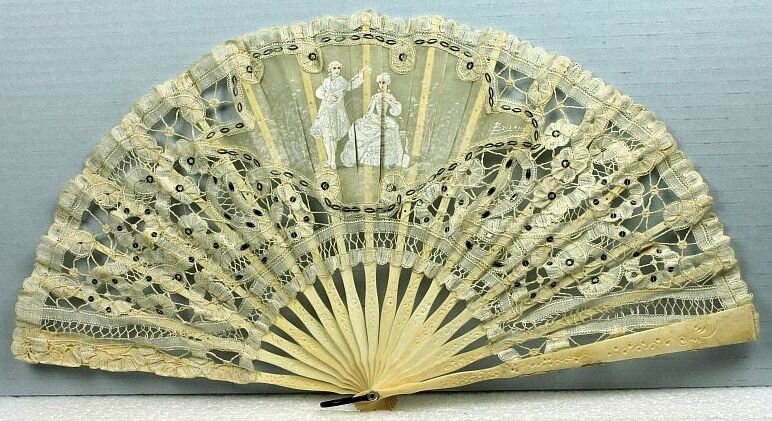

By the mid-1500s, Europe had begun to make its own fans and Paris soon became the center of fan production. By the 1700s, the art of the European fashion fan had reached its height. Gold, silver, ivory, silk and precious gems were used in making fans, as were simpler materials such as wood and leather.

Many 18th Century pleated and brise fans were painted with reproductions of masterpieces. After the discovery of Pompeii in 1748, fans blossomed with neoclassical motifs. Later in the century, the success of the Montgolfier brothers` hot-air balloon made that lofty subject popular with fan artists.

From the beginning of the 18th Century, wealthy brides and widows were equipped with delicate marriage and dour mourning fans. Other fans commemorated national events, such as inaugurations or the deaths of public figures.

Advances in 18th Century printing technology brought the fan within reach of the masses. A novel type of printed fan known as an aide-memoire (a French phrase meaning ”prompt the memory”) was popular between 1780 and 1820. These instructional fans carried printed details on everything from how to flirt to the biological parts of a flower.

During the early years of the Victorian era, fan types from the 1700s and earlier returned to dominate the market. Lithographed, hand-colored fans imitated hand-drawn versions of earlier eras.

Americans who had imported European fans from the late 1600s to the mid-1800s, joined the fan-making fray soon after the Civil War. In 1867, Hunt Fan Co. opened in Massachusetts and made-in-America fans began to acquire a following.

During the last decades of the 1800s many fan makers, gripped by a widespread nostalgia for the artistic days before the Industrial Revolution, copied the elaborate painted fans of the previous century. Although the painting on these fans lacked the refinement of the 1700s examples, these fans today continue to confuse unwary collectors.

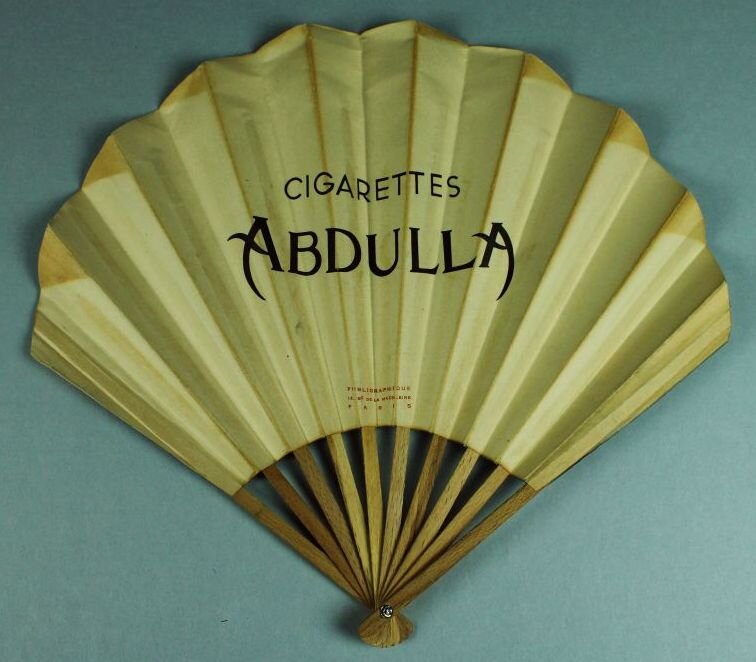

Advertising fans soon joined art with avarice in an outpouring of promotional gimmicks that peaked at the turn of the century. These mass-produced fans remained popular until the 1940s.

Fans retained their favored position until well into the 1930s, and well- known artists designed examples that expressed both the sinuous nature of art nouveau and the clean angularity of Art Deco. As fashion catapulted into the modern age, however, the fan suddenly seemed out of place.

Advertising fans are the easiest to find. The American hand-screen type can still be bought for less than $5. Specialty versions, such as one showing the Dionne quintuplets, born in the 1930s, may cost $25 to $35. Other types of fans available for less than $100 include the spangled and sequined fans made between 1895 and World War I; ostrich-feather fans, made from the late 1800s to the 1930s; painted satin fans, made from the 1860s to around 1910.

Beginning collectors should be wary of ignorant or unscrupulous dealers. Many fans made in the 1950s and 1960s have plastic sticks with printed leaves that have been hand-colored, and some people try to sell these as antiques.

(SOURCE)